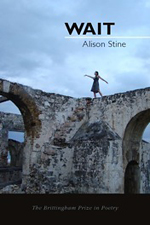

Review | Wait, by Alison Stine

University of Wisconsin Press, 2011

|

For all the dialogue and guesswork on the elements of a successful first book, little exists on the elements of a second collection—the inevitable (and often rushed) successor. Alison Stine’s Wait arrives just two years after her debut, Ohio Violence (University of North Texas Press, 2009), and though the collections work on analogous forms with generally midwestern—though hardly road-weary—imagery, the widening of Stine’s ambit relies upon compression: not only of language but also of time.

Katie Ford, in a conversation published in Blackbird v8n2, said: “The amazing thing about writing a first book is that you have your whole life pressing on you, so you have all of it to use. You only get to do that, kind of, once. Some poets do it again and again, and the fear when you’re writing your second book is that you’ll rewrite your first.” For some poets, this fear drives a radical departure from the style of their first collections—Ashbery, perhaps, in his move from Some Trees to The Tennis Court Oath—or, more radically, a disownment of the work, à la Robert Hayden who deemed his first book to be “prentice work” and refused to acknowledge its place in his canon. Other poets don’t share in this fear; for them, the second book makes a second lap around the same track, a chance—though not a guarantee—to quicken the pace and look all the more graceful doing it.

Wait, Stine tells us, spans the year before a woman’s marriage—a brief time frame in contrast to Ohio Violence—a first collection which has, as Katie Ford suggests, an entire life available to use as subject matter: public school, the football coach, parents, coming into one’s sexuality, the death of a friend, the old house, etc. The relatively narrowed focus of Wait allows Stine to pause on her subjects so that she not only sees the surface but also the complex structure of emotion and intention beneath an individual or action. This focus makes for a more mature understanding and thus, reckoning from the speaker.

“All our meaningful speech would not heat / a cup of water,” Stine begins “Rabbit of the World,” a prescient and deeply succinct sonnet that comments on the failure of words—arguably, in the mode of ars poetica, perhaps after MacLeish’s “A poem should not mean / but be”—and uses the poetic form to portend the unknown and quickening force. The sonnet form becomes the body-vessel through which foresight and memory surge:

And I have already failed.

At the end of our lives these words

will mean nothing—only if you read,

and remember the call of my skin,

how I willed you. I have seen on the pay

road, motorists turn, those who stop

for nothing slow at the sight of a hill:

Somerset County, the wind farm where

blades arch as the body, steady the air, spin

it to sparks. Imagine what it is like for me

to want you, to wait. Harbinger, rabbit

of the world, red eye flashing as if to warn:

the power that is coming will make no sound.

A poem from the first collection, in comparison, like “Homer, Ohio,” a twelve-line ghost sonnet, shows how Stine has honed her control over form and widened the resonance of the subject matter. Both poems weave the address to the lover with the external: a place (Somerset County in western Pennsylvania and Homer, Ohio); the road; the distant, almost spectral, others witnessed by the speaker (“I have seen on the pay / road, motorists turn, those who stop / for nothing” and “Women, I have seen / your sign”); an object or symbol of cutting (“blades” and “teeth”); the vatic symbolism of the eyes (“red eye flashing as if to warn” and the allusion to the blind poet Homer); and the premonition of change (“the power that is coming” and “a gift that is turning”). So what has Stine improved upon? What is she doing differently? Not only does the more recent poem possess a greater economy of syllables—a more definite, if not more propulsive form—the move from a time-span narrative toward a moment-based lyricism intensifies the speaker’s voice. If these two poems were films, “Homer, Ohio” would unfold through voiceover where “Rabbit of the World” would show the mouth, the person, in the act of speaking.

In “Rabbit of the World,” and many other poems in Wait, the conclusion is beyond the self, out of the control of the poet, and even more importantly, the others who surround the speaker. Many of the poems in Ohio Violence end with the imperative (“I love you. Live.”) or something known without question (“I am learning // whomever we love, we are left this way, halved”). This kind of youthful overconfidence muscles out its conclusion and leaves little room for a sustained, after-poem resonance. The maturation of Stine’s voice in Wait gives more credence to the lost and ineffable and echoes within that empty space: “My body / dissolved like grains,” in “Your Marriage”; “How / could they know, like me, they // were being asked for the answer?” in “The Ripper’s Bride”; or, in “The Interpreter,” the literal displacement of one lost thing for another:

There are

not signs for everything, the interpreter

said when asked if she ever forgot words.

You make them up, get close enough.

Sign insect if you have forgotten cicada.

Later, you can go back, sign seven year,

sign seeking heat. Sign burrowing, sign gone.

The two forms used by Stine—the singular stanza and the alternation between a couplet and a single, often jagged line—work to develop this metaphor for loss and the ineffable. The singular stanza attempts to ground and hold together something that’s slipping away, as seen in poems like “The Interpreter,” or “Scissors, Hammer, Hoof Pick, Awl” in which the speaker copes with a family problem through shopping—“So I bought a poodle. / I bought a pashmina. I bought a locksmith’s hour / to alter the locks”—or “Impetus,” which ends with a scant and hasty harvest:

Each year

we have reason to take some part

away. I hurried to bring it inside

to the table. Didn’t I deserve that, one

lobed fruit, to split, to swallow, myself?

The second form gives the illusion of movement. The subjects, therefore, slip away as the poems progress, such as “Velata,” about the woman long believed to be Raphael’s mistress but who, in secret, might actually have married the painter:

Myrtle and quince, the secret

gathers between them like a blister,

capped in blood. Here is his

name on a blue sash banding

her arm in two: flesh above, flesh

below. Here is a bruise, butterfly

and later:

Is this what men do, make

mistresses from wives? His students hurry:

scrub the ring off, scrub the ring off,

scrub the ring off, scrub the ring—

This fleeting feeling, sustained by both the content and form, gives the poems a kind of elegiac sensibility, though the lament is often sung for the unmarried self. That said, Stine depicts marriage as a ceremony of rebirth, as evident in the end of the collection’s first poem, “Wife”:

The birds landed

in our braided hair, and the men

called but could not find us. You

were coming. You were coming.

I didn’t know. I would have curled

in a rabbit whorl, a mouse nest,

in a leaf-spilled shade. I am a bird

in the field and I want you to find me.

I want you to find me. Tell me wait.

Here, the form shows movement within the speaker, the progression of the self, transformation. With this poem and the others in Wait, the forms push the content beyond mere lyricism or, in some cases, narrative. Instead, the forms create a space in which the voice of the speaker resonates, returns in echoes beyond the poem.

Stine’s increased awareness of how her two signature forms work with her subject matter makes Wait a more substantive collection than Ohio Violence, and the similarities between the two books may simply be a product of Stine’s innate concerns. In his essay “On Voice and Revision,” Mark Cox says, “To my mind, my body of work is really one long poem,” and though not all poets, including Stine, can easily boil down their canon to one composite, Cox insists that, although each collection ultimately has a beginning and an end, the poet works poem by poem, from the very first to the very last, without bookends; and this process, he attributes to the authenticity of the poet’s voice:

No matter how conflicted the attitude or content in question, there is a multidimensional wholeness at the heart of authenticity, a relatively conscious synthesis of all the voices that make up the chorus of a person’s being

For Stine, the poems of Wait bear witness to this refined authenticity, a voice extending her register and, therefore making more dynamic the song. For this reason, the collection honors the spark of her earlier work without duplicating it—dynamic not only in the evolution of her career but also as a single work: midwestern though not bland, full of gothic nuances and associative layering, as determined and complicated as the wife entering her marriage, a life not just for the self, but also for another. ![]()

Alison Stine is the author of two collections of poetry: Wait (University of Wisconsin Press, 2011), which won the 2011 Brittingham Prize in Poetry, and Ohio Violence (University of North Texas Press, 2009), which won the 2008 Vassar Miller Prize in Poetry. She is also the author of one chapbook, Lot of My Sister (Kent State University Press, 2001), which won the Wick Poetry Chapbook Competition.