United by Ritual

A version of this essay appears as the foreword to Alfred Gallery's TableSpace exhibition catalog. Blackbird has excerpted exhibition images and quotes from (or about) select work from each artist to display inline with Risatti's introductory text. At the essay's foot, the entire TableSpace catalog is availble for download.

TableSpace is an exhibition of functional ceramics by fourteen artists from North America, Europe, and Asia. The works represent a wide range of artistic possibilities, certainly in terms of material and aesthetic points of view—some works are humorous; some are based in a design/machine aesthetic, even reflecting digital aids; others take their cue from historical objects as they seek to extend established traditions; still others seek an independent path by exploring material and form in new ways.

|

|

| Andy Brayman Black Spiral Vase 11 x 10.5 x 10.5 in porcelain |

|

|

|

| Andy Brayman White Bowl with Dots 4.5 x 8 x 7 in porcelain Off-White Bowl with Half Blue Rim 4.5 x 8 x 7 in porcelain |

“ . . . These drawings are first created digitally through the use of a computer program that takes sensor data from the natural world and converts it into abstracted geometries. Light, temperature, humidity, and wind speed just outside my studio are used in conjunction with software to drive the specifics of the marks on the pots.” |

|

|

| Robert Sutherland Jar 12 x 10.5 x 10.5 in porcelain |

“Form and function have always been of interest to me. Making pottery is and was about needing an object to eat from—an object that was plain, simple, and most importantly functional.” —Robert Sutherland |

|

| Robert Sutherland Jar (detail) 12 x 10.5 x 10.5 in in porcelain |

Aside from the works themselves, the title, TableSpace, also prompts some interesting observations that have not only to do with the quality of the objects presented, but with the concept underlying the exhibition itself.

|

|

| Ole Jensen Teapot 7.9 x 5.9 x 7.9 in Cup 3.5 x 2.8 x 4.3 in Colander 7.7 x 8.7 x 9.4 in Juice Jug 5.5 X 5.1 X 6.7 in faïence Royal Copenhagen |

“Clay is almost the ultimate material for mediation via form. The Danish concept formsprog [form language], or artistic idiom, is virtually contained in the clay itself.” —Ole Jensen |

As curator Linda Sikora writes, the work in the exhibition “addresses the subject of function, and through this, implicates the site of ‘table’ or other like situations.” Her observation, it seems to me, points to the heart of the matter. For what unites all of these objects, regardless of their varied physical forms, is that all of their makers seem drawn to a similar idea of table. That is, they see it as a specific kind of space—a specific locale, if you like, wherein their objects exist as participants in a very important and very human drama. In other words, to these artists this locale is more than just that physical space marked out by the literal plane of a tabletop. To them its dimensions are grander, linked more to a philosophical-humanistic concept than to anything as simple and clearly defined as a tangible, concrete space.

|

|

| Ole Jensen | “Some were made as hand-made unique items in my own workshop, others as limited editions and yet others as industrial design. For me, all this coheres and the articles have been brought together as one complex composition—a family made up of what seems at first glance to be modest pottery . . . ” —Ole Jensen |

While the roots of this concept are buried somewhere deep in our collective consciousness, we can begin to understand something of what is involved here if we remember that nourishing the body through food and drink is arguably the most basic of instinctive drives. The need for nourishment, after all, begins at birth (in fact, before birth) and continues until death. That humans share this primal instinct with all other living things on the planet underscores its importance. The instinct for nourishment is a primal, a priori instinct, not something learned through socialization.

|

|

| Sonngard Marcks Bowl, Vegetables on Persian Cloth (detail) 3.5 x 14 x 14 in faïence |

“I am always interested in several levels: the plasticity of the pieces along with the painting and their interaction. You should never be able to take in everything at first glance. The beautiful surface should invite you to explore, seduce you, and offer as much depth as possible.” —Sonngard Marcks |

In other words, it is not a cultural construct and hence something we can embrace or dismiss at will. Rather, it is an involuntary, unreasoned action (e.g. eating) as a response to certain stimuli (e.g. hunger). Thus in a very real sense, it is nature guiding our actions, nature speaking directly to us through our bodies. In this sense we cannot speak of a human nature—there is no such thing. Human and nature are opposites, because humanness can only be achieved by the taming of nature (e.g. by taming that natural instinct that programs the strong to devour the weak in a quest for survival).

|

|

| Sonngard Marcks Box With Yellow Paper 19 x 6 x 6 in faïence |

“Over the years, I have focused my painting on the topics inherent in nature—and precise observation dominates here—the stylisation given by nature offering me endless inspiration.” —Sonngard Marcks |

As an example of nature versus culture, the hunger-nourishment equation is one in which nature clearly has the upper hand. However, as the objects in TableSpace demonstrate, there is more involved here than simply giving into nature, of letting nature have its way. For even though we cannot resist nature’s imperatives, we have been able to transform this specific imperative into something beyond mere nature. We have been able to make it into an element of culture, and thus an expression of our humanness standing in opposition to nature.

|

|

| Sam Uhlick Jar 13 x 12 x 12 in stoneware |

“ . . . although form, function, pattern, and colour are all important in pottery, it is the warmth and spirit that can only be experienced through handling and use which are most important. Good pottery must have a liveliness and interest which goes beyond technical mastery.” —Sam Uhlick |

|

|

| Lisa Orr Compote Vase Centerpiece (detail) 15 x 13.5 x 13.5 in earthenware |

“I have made the work that my eye craves to absorb and that, to me, will best enhance a freshly prepared meal. This display of color at the table represents a successful and healthy garden and anticipates something delicious.” —Lisa Orr |

The question is, of course, “In what way is the table a cultural expression of our humanness, as apart from, say, simply a platform upon which to place certain functional objects?” How does it differ, for example, from something like the gallery pedestal to which it seems related? For one thing, the gallery pedestal is designed to display objects so that they can be best seen by a viewer, usually one who is standing. This requirement determines both the pedestal’s shape and its height.

|

|

| Sarah Jaeger Blue Decorated Ware porcelain White Ware porcelain |

“I am a thrower, and my concern is with the volume and sense of interior space of my pots. My decoration is about patterns that can wrap themselves like skins around the surfaces of the pots, no front or back, beginning or end.” —Sarah Jaeger |

Another difference is that objects and pedestal remain separate entities, one being little more than a prop for the other; there is no intentional interaction between the two, neither physical nor psychological. The tabletop, on the other hand, is a place where certain types of functional objects are intended to be used; it is use that determines the table’s shape and height. Also, unlike the gallery pedestal, the tabletop implies both use and user and, therefore, a physical and psychological connection between itself and object and between use and user. Because of this, the tabletop must be understood as more than just a physical support for objects, it must be understood as a conceptual space, a site, a locale, in which something happens with and through certain types of objects: platters, plates, cups, pitchers, etc. Furthermore, this something happens according to specific rules of behavior that have a social dimension to them because they involve social interaction.

|

|

| Kari Radasch Blue & Green 5.25 x 28 x 22 in terra cotta silicon rubber |

“On the one hand I see my collections of pots as three-dimensional snapshots, similar to a still life, but they are dishes placed within a table-scape. They suggest nourishment and sustenance and, due to the intimate setting for two, also imply familiarity and conversation.” —Kari Radasch |

It is this sense of social interaction that forms the philosophical-humanistic concept underlying the culture of the tabletop evident in the objects in this exhibition as well as their placement. For example, there are matching sets of objects including teapots and teacups as well as matching pitchers, plates and platters; there is even the pairing of objects and the arrangement of objects into place settings. All of this implies multiple users and thereby underscores the tabletop as a site for social interaction, as that place where something as basic as food and drink are shared with others.

|

|

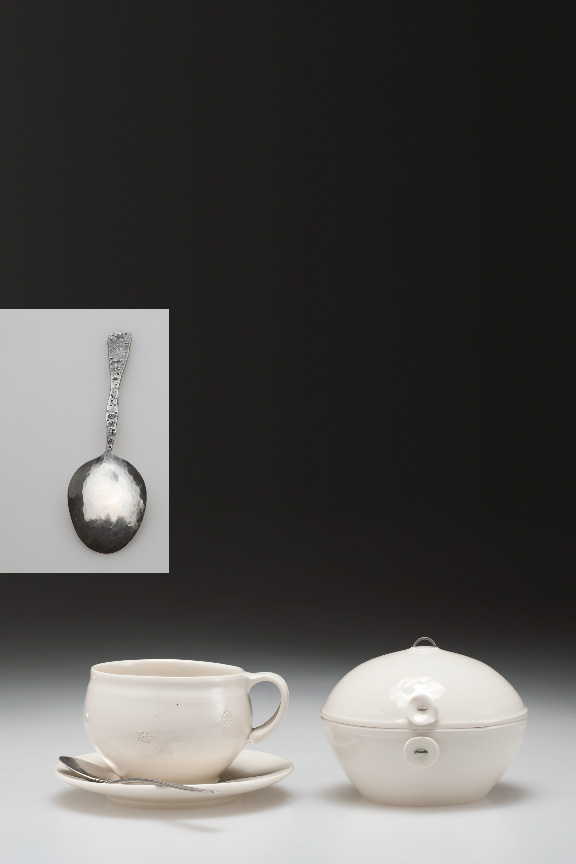

| Gary Noffke Spoon 1.5 x 1.5 x 5.25 in hot forged sterling Sandy Simon Cup and Saucer 3.5 x 5.25 x 5.25 in bone china Covered Jar 4 x 5 x 5 in porcelain, nichrome wire |

“ . . . the art that moves me to gratitude, to communicating and sharing my spirit, is the art of the functional pot. . . . Objects carry our energy; pots carry a part of us. They carry not just what the maker brings to it, but also what the user brings.” |

This sense of sharing pervades the objects in TableSpace and is part of a very human ritual, one in which guests at table, even one’s enemies, are honored not only by being fed, but by being served first. As a ritual act which puts the other before the self, it implicitly recognizes the other as a fellow human being. This is the essence of being human, for it is man resisting the dictates of nature, man acting against nature and the natural instinct to put the self before the other. Because of this, the ritual of sharing at table, which forms the culture of the tabletop, must be seen as a metaphorical as well as a real act of communal being, one that forms the basis of the family unit as well as any larger sense of community, both sacred and secular.

|

|

| Mark Pharis Tray 5.75 x 21.25 x 19 in earthenware |

“Surface exploration is a halting endeavor for me. I continue to pursue it but my default setting is simplicity, a reductive stance, and I find I am most comfortable there.” |

In a very real sense then, the space of the table, as a communal space, makes demands on artists and participants alike. The demands it makes on participants are that they have a sense of what is proper and fitting as members of a community with others, that they comport themselves with a degree of decorum befitting the ritual in which they are participants.

|

|

|

| Tomoo Hamada Plate 1.5 x 11 x 11 in stoneware Plate 1.5 x 10.5 x 10.5 in stoneware |

“While Tomoo’s pottery remains functional, with vessels being central to his practice, he experiments with new forms and considers the decorative function of his work. . . . To Tomoo, repetition is a self-expression that mimics the wheel as well as generational knowledge and respect.” —Melissa Ferris Gallery Associate, Pucker Gallery |

For artists, the demand is to make objects whose taste and refinement communicate the metaphorical importance of this space as a philosophical-humanistic concept. That this can be done is clearly evident in the works in the TableSpace exhibition.

|

|

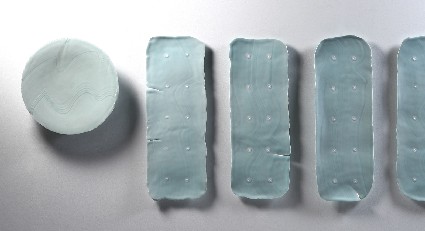

| Takeshi Yasuda Plateau 3.3 x 15.2 x 15.2 in qingbai porcelain Platters 1 x 9.5 x 25 in qingbai porcelain |

“Even today serving food on an interesting object rather than standard table-ware is not an unusual occurence even among common people. . . . For Japanese, fuctionality is not the attribute of the object but of one’s imagination.” —Takeshi Yasuda |

In their aesthetic quality and sense of propriety one can even sense faint traces of those sacred implements used in religious rituals—rituals which, interestingly, re-enact this same communal space of the table, but on the level of the spiritual; here one has only to think of the Christian Last Supper and Mass, or the Buddhist tea ceremony.

|

|

| Paul Eshelman Individual Teapot 5 x 9 x 4 in red stoneware |

“Functional pottery is my cultural attempt, through the material of clay, to bring order and human dignity to the merely physical act of consuming food and drink. . . . I imagine people at a dinner table, work space, or office cubicle where food and drink are served and humanized by a hospitable, well-ordered pot.” —Paul Eshelman |

|

|

| Paul Kotula Setting for One 7.5 x 23.5 x 20 in Setting for One 4.5 x 27 x 22 in laminated wood, glass, stoneware |

“We exist in intimate space, as physical beings whose sustenance is based on the nourishment of real experience. I make to offer and remind people of that.” —Paul Kotula |

That functional craft objects can encompass all of this is no small thing, for in doing so the metaphorical demands of the tabletop ripple outward, influencing the larger society as well, all the way from the romantic dinner for two, to the royal banquet, to the official diplomatic state dinner. In this way, the functional craft object, as part of the culture of the table, takes on an importance that goes to the very core of civilized society. ![]()

TableSpace Catalog [pdf]