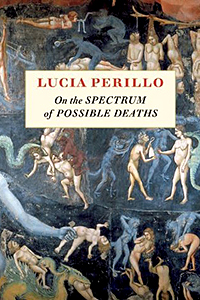

Review | On the Spectrum of Possible Deaths, by Lucia Perillo

Copper Canyon Press, 2012

|

|

In Plato’s Phaedo, the condemned Socrates tells his followers,

all who actually engage in philosophy aright are practicing nothing other than dying and being dead

or, in informal translation,

Philosophy is a preparation for death.

To argue that the practice of poetry has similar implications reeks of early Romanticism, but Roethke asserts the converse:

To write poetry: you have to be prepared to die.

In her fifth collection, On the Spectrum of Possible Deaths, Lucia Perillo shrugs off all this postulation about mortality and writing:

When you spend many hours alone in a room

you have more than the usual chances to disgust yourself—

this is the problem of the body, not that it is mortal

but that it is mortifying.

Writing poetry then doesn’t necessarily prepare one for death, nor does one need to be prepared to die to write it. In fact, as Victor the Shaman, the title character in one of Perillo’s poems, suggests, “No matter how many rounds you go in practice, / . . . you always come out unprepared.” Rather, the solitary practice of writing (think of Dickinson, “Repaired of all but Loneliness”), especially when coupled with a debilitating disease like multiple sclerosis from which Perillo suffers, allows one not only the time and space, but also the necessity, to consider the body, to be “repelled by it.” Flaubert, who suffered from epilepsy and subsequently retired to near seclusion in Croisset, also spoke of the writer’s solitude and the body in a letter to George Sand:

I have palpitations of the heart for nothing . . . All that results from our charming profession. That is what it means to torment the soul and the body. But perhaps this torment is our proper lot here below?

Though Perillo never calls her lot a torment and likewise never treats her disease as a hazard of the profession, as Flaubert did, at moments her speaker succumbs to the pressures of solitude and infirmity, as in “Freak-Out” with its “distillery of anguish”; and “After Reading The Tibetan Book of the Dead,” in which the speaker says, “dear whom: / the weight of being is too much.”

In “Samara,” however, awareness, especially of death, means survival:

Somewhere Darwin speculates that happiness

should be the outcome of his theory—those who take pleasure

will produce offspring who’ll take pleasure,though he concedes the advantage of the animal who keeps death in mind

and so is vigilant.And doesn’t vigilance call for

at least an ounce of expectation,

imagining the lion’s tooth inside your neck already . . .

That said, Spectrum resists acting as a mere memento mori, in the tradition of Merwin’s poised self-elegy, “For the Anniversary of My Death” (“Every year without knowing it I have passed the day / When the last fires will wave to me”). Likewise, one may make superficial comparisons between the collection’s title and a number of depictions of the danse macabre, but Perillo alludes to so much—history, music, art, science, and poetry—that a comparison to one mode of expression like the danse macabre ignores the complexity of her poems.

At turns complacent—“the self / is the darling’s darling”—and then bitter—“my envy / aimed at those who drift inside the bubble of no-trouble”—she’s buoyant elsewhere, as when she describes falling samara, the fruit of the maple:

hard to believe the earth-engine capable of such invention,

that the process of mutation and dispersal

will not only formulate the right equationsbut that when they finally arrive they’ll be so

. . . giddy?

Perillo’s humor may at first startle the reader, especially up against the dark subject matter, but it serves as comic relief for the reader and, for Perillo, as a mechanism to stave off loneliness, to entertain oneself in solitude. Her wit ranges from irreverence—

And when I flip open the back covers of their books,

the famous lady poets all have shiny hair.he will not let a helmet wreck his hair—

why does the brain have to be buried

in the prettiest place? You little shit . . .

—to wacky associative leaps—

The popcorn here is not just bad—

for years the hopper has accrued its crud

so that sometimes you crunch down on what

tastes like a greasy tractor boltand are transported to a former Soviet republic

instead of some seedy part of Paris.

—to clever phrasing, like the “red-dye-number-toxic / bright and shiny food” at the Chinese restaurant in “300D,” and to situational comedy—

The freak-out wants wide open space,

though the rules call for containment—there are the genuine police to be considered,

which is why I recommend the empty vestibulethough there is something to be said for freaking-out

if the meadow is willing to have youfacedown in it,

mouth open to the dry summer dirt.

There are many moments in which the bittersweet humor stems from solitude and the body, as in “Heronry”:

Now my body has become so stylish in the ancient way—didn’t Oedipus

also have a bloated foot? Yes,

I remember him tied by the ankle in a tree, after his father heard the terrible

prophecy and left him hanging

for the animals to peck and lap, same way the dog likes to lap my bloated foot

when I take off the special socks

meant to squeeze it down. He likes to eat my epidermal cells before they fly

off on the air that moves on through

the tallest trees one valley south, where great blue herons build their nests

and ride on small twigs up—then gently

do their legs glide down my binoculars’ field of view.

As panoramically as the tone shifts here—the conversational “Yes,” the cheeky “special socks,” the scientific “epidermal,” and the elegiac rendering of the skin cells floating off toward the heronry—the poem doesn’t affect an omniscient point of view. Rather, it follows the natural progression of the speaker’s imaginings.

The only beings encountered thus far in the poem are animals, with whom she cannot fully connect and, yet, to whom she gives her “first lament.” The poems are relatively unpopulated; other people emerge from memory or books; and when she encounters other humans, she cannot communicate with them. The autistic girl at the precinct in “The Caucus” only recites lines from her socialization cards, and the father in “My Father Kept the TV On” reads books “to escape us / who were the shackles that the plodding days / latched on to them.”

Though distanced from other people, Perillo’s capacity for empathy remains as robust as in her previous collections. She often depicts empathy with a physical image, as in “Proximity to Meaningful Spectacle”: “I swim with the old ladies” and

We ride the wacky noodles

through blue pastures

lit by chemicals—I like to go under in my goggles

to watch their them-ness bleed

into my me

Water becomes the medium that blends individuals. How is the “me” different now from the “them”? This question leads to another that’s important to the collection: How does death differ for each of us? Consider a more ominous ride, in “Auntie Roach”:

One day George Washington rides around Mount Vernon

for five hours on his horse, the next

he’s making his auspicious exodus

on the spectrum of possible death.

The poem then describes a range of deaths, most of them historical figures like Rasputin who’s been poisoned and now shot and thrown into “the frozen Neva.”

Now, he must have howled

while his giblets leaked, though the cold

is reputed to be kind. Sliding his end

toward a numeral less horrible; it falls

say as a six on a scale of zero to ten?

And, winding up:

Shakespeare went out drinking, caught a fever,

ding! Odds are we’ll be addled—

what kind of number can be put on that?

One with endless decimals,

unless you luck into some kind woman,

maker of the minimum wage, black or brown and brave enough

to face your final wreck?

The “final wreck,” the devastation of the body before death, haunts the collection. Both fear and inevitability, it provides motivation for the foreboding images in the collection. Some poems, like “Cold Snap, November,” recall the Dutch vanitas paintings, though marked with Perillo’s humor.

This year made it almost to December without a frost to deflate the dahlias

and though I stared for hours at the psychedelia of their petals,

trying to coax them to apply their shock-paddles to my heart,

it wasn’t working. Until one morning when

I found them black and staggering in their pails,

charred marionettes, twist-tied to their stakes, I apologize

for being less turned-on by the thing than by its going.

Not the sunset

but afterward when we stand dusted with the sunset’s silt,and not the surgical theater, even with its handsome anesthesiologist

in blue dustcap and booties—no,his after’s what I’m buzzed by, the black slide into nothing

(well, someone ought to speak for it).

Whether the end of this quote references death or the experience of going under anesthesia, Perillo fixates on the liminal, the borders that one must cross alone, perhaps after Dickinson’s idea that “Pang is good / As near as memory —” In this way, the collection seems to call attention not to solitude as much as to its opposite. The solitude here shows the value of what once was, colored not by bitterness but by gratitude. “[E]ach truth has its stage,” wrote Roethke. What was shows the value of what’s now, and what’s now sweetens what was.

More precise than her previous collections, On the Spectrum of Possible Deaths moves deftly between subjects—from robotic seeds to a punk skateboarder, a photograph of the grandfather to a wildlife viewing station—without as much exposition or as many prepositional signposts as in The Body Mutinies and with more thematic focus than Inseminating the Elephant. At every turn, Perillo considers the reader—her aim always on clarity and sharp images positioned on propulsive lines. While immensely quotable, she resists platitudes by questioning absolutes and undermining the too-serious with humor.

In On the Spectrum of Possible Deaths, we find a woman who has come to terms with her circumstances, one who cares deeply for the world, including her place in it. She finds poetry then not so much a preparation for death as a space in which the poet can exist without fearing death, beyond death.

“[O]h shut up,” Perillo writes. It’s easy. “The rule is: you can’t nullify the world / in the middle of your singing.” ![]()

Lucia Perillo’s most recent publications include a book of poetry, On the Spectrum of Possible Deaths (Copper Canyon Press, 2012), and a book of short fiction, Happiness Is a Chemical in the Brain (W. W. Norton and Company, 2012). She has taught at Syracuse University, Saint Martin’s College, Warren Wilson College, and Southern Illinois University.