Portrait Statue of Caligula

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) in Richmond, Virginia, possesses one of the finest and most important images of a Roman emperor in North America, a full-length statue of the Emperor Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, more popularly known as “Caligula” (“Little Boot”).

|

Portrait Statue of Emperor Gaius (“Caligula”), 37–41 CE |

The statue’s beauty lies in the exquisite craftsmanship of the stone carving, so subtle that it conveys a sense of the overlapping layers of clothing that Caligula wears and even records “press lines”—the lines that an actual toga would have had after being folded and stored in a chest when it was not in use and that are clearly distinguishable from the folds of the toga.

|

Horizontal press lines along the left side of Caligula’s toga |

The statue’s importance lies in the fact that Caligula ruled for less than four years before he was assassinated, and he was so unpopular that almost all images of him were destroyed, defaced, or recarved into likenesses of more acceptable Romans. Today, only two full-length statues of Caligula are known, the example in Richmond’s VMFA and the portrait of a youthful Caligula found in Gortyn, Crete (the Roman capital of that region under Caligula’s rule).

The Gortyn statue, like VMFA’s, shows Caligula wearing a toga, but in this case his head is veiled, indicating that he is taking part in a religious ceremony (probably his outstretched right hand held a patera for pouring libations). The youthfulness of the Gortyn Caligula suggests that the statue was made before Caligula became Princeps, “First Citizen,” the official title of the early emperors.

|

| Portrait Statue of the young Caligula capite velato, circa 32 CE, Gortyn, Crete Photo by Peter Schertz, VMFA curator of ancient art |

In 2010, the University of Virginia and VMFA received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to undertake new technical studies of the Richmond Caligula under the codirection of Dr. Bernie Frischer, UVA professor of classics and art history, and myself.

The primary goal of the technical studies was to make a 3D model of the statue and to study its ancient polychromy, the added colors that were a part of all ancient marble statues.

A second goal of the project was to promote a better understanding of the statue’s ancient topographical context, appearance, and cultural significance. We assembled an international team of scholars to address questions of the original appearance of the statue, its ancient context and rediscovery in the nineteenth century, and historical issues surrounding Caligula’s life and reign.

|

Caligula team members in front of the statue, December 3, 2011 |

VMFA’s Caligula was a particularly strong candidate for such an intense study because much of the recent scholarship on Greek and Roman polychromy has concentrated on works of Greek art (many of which were showcased in the traveling exhibition—and catalogue—Gods in Color, originating from the work of German archeologist Vinenz Brinkman) so the study of a major example of Roman art could significantly add to our knowledge.

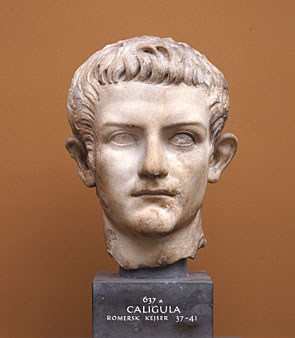

Also, one of the most fascinating studies of a polychromed Roman work, which precedes the study of the Richmond statue, was on a portrait of Caligula at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, an art museum in Copenhagen with a focus on ancient sculpture. This study and restoration of a bust of Caligula was conducted by the Copenhagen Polychromy Network, an interdisciplinary research partnership. Below is the marble portrait and the color reconstruction done by CPN, one of the early efforts of that group to show that “Greek and Roman sculptures were colorful.”

|

|

|

Portrait head of Caligula (left) and modern reconstruction (right) |

||

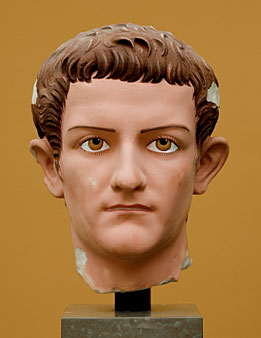

Building on such previous scholarship, the first step in the team’s study of the VMFA Caligula was to create a 3D digital model, known as the “State Model,” that recorded the current appearance of the statue and which served as the basis for hypothetical reconstructions of the ancient statue. The work was done by Peter Kennedy and Greg Chaprnka of Direct Dimensions, a private company based in Maryland.

|

|

|

| VMFA Caligula |

State Model, 3D digital scan |

At the same time that we scanned the statue for a digital model, Dr. Mark Abbe, assistant professor of ancient art history at the Lamar Dodd School of Art at the University of Georgia, examined the surface for traces of tool marks and polychromy using raking light, UV light, and photo-induced luminescence.

This examination yielded new information regarding previous restorations to the statue in the form of the decipherment of a previously known but unintelligible inscription on the left arm. Only with the use of raking light were we able to clearly read the inscription, “1843.” Following Maria Grazia Picozzi’s (associate professor of the history of archeology at the University of Rome) archival research on the statue’s history, we were able to relate this inscription to the nineteenth century restoration of the statue.

|

|

|

Surface of reworked left arm in ambient (left) and raking light (right) | |

||

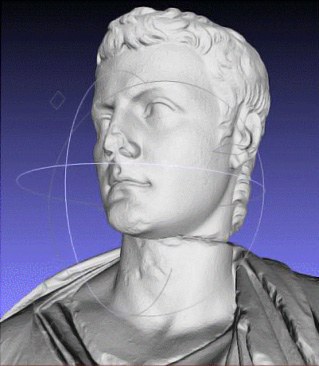

The great hope in undertaking this project, however, was that we would find sufficient traces of polychromy to reconstruct the clothing of a Roman emperor. In this we were disappointed. Only two small traces of polychromy were identified, both of them in deep vertical folds of drapery across the upper chest. These traces were located using photo-induced luminescence, a recently developed technique used to identify traces of Egyptian blue, a pigment which many consider to be the world’s first synthetic color.

|

|

|

Details of microscopic particles of red/pink madder lake (left) and Egyptian blue (right) |

||

What was gratifying, however, is that the combination of pink madder and Egyptian blue were used to produce various shades of purple, according to both ancient written sources and modern analyses of purple on other works of ancient art. Purple is especially important in the Roman context, as Romans indicated senatorial rank by the addition of a purple stripe to their togas (the toga praetexta) while the more elaborate toga purpurea (all purple toga with gold embroidery) and toga picta (painted, or pictured, toga) were even more prestigious.

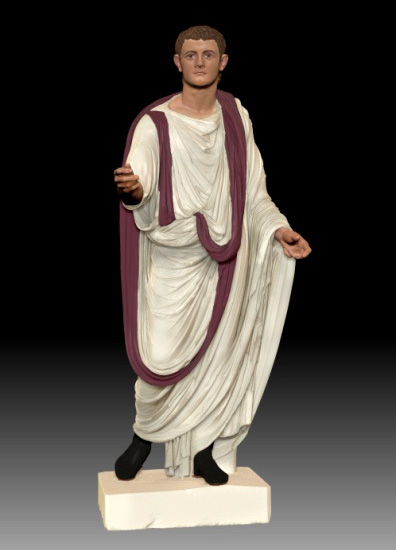

In making our hypothetical digital reconstructions of VMFA’s Caligula, we looked at ancient comparisons and literary sources to propose two possibilities; first, Caligula in a more senatorial guise with the black boots and toga praetext:

|

| Digital reconstruction VMFA Portrait Statue of Caligula wearing a toga praetexta. |

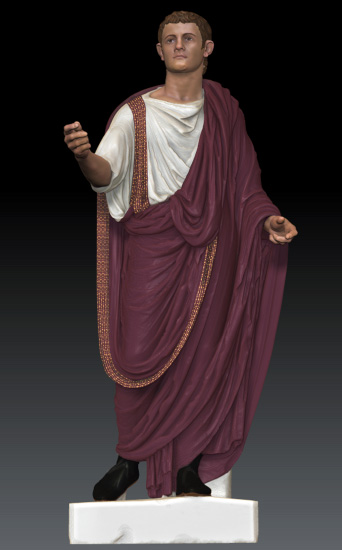

And second, Caligula in a more imperial guise, with black boots and a gold-embroidered toga purpurea:

|

| Digital reconstruction VMFA Portrait Statue of Caligula wearing a toga purpurea with gold embroidery |

The NEH-funded study of Caligula’s polychromy led directly to my decision that we should undertake a new conservation campaign focused on the statue with two goals: (1) to determine whether the head and body of the statue are from a single block of marble and, therefore, “belong” and (2) to adjust the position of the head. To this end, conservators undid the 1971 restoration of the head in order to physically separate the head from the body. This involved the removal of a copper rod that probably dated to the statue’s nineteenth century restoration. This rod had been inserted in holes drilled in the torso and head and was held in place by a hard epoxy that had to be removed by mechanical means.

Researchers took small samples of marble from both sides of the exposed surfaces of the break for stable isotopic analysis. (Raking samples from the interior of the break ensured that the marble samples had not been contaminated by environmental factors). The analysis revealed an almost exact correlation of the marble samples, leaving no reasonable doubt that the body and head are from a single block of Parianlyknites marble. This fine-grained, pure white marble was quarried on the Aegean island of Paros and was highly prized in antiquity. Among other well-known statues carved from lyknites is the statue of Rome’s first emperor (and Caligula’s great-grandfather) known as the Augustus Prima Porta, which was found in a private villa of Augustus’s wife, Livia.

|

|

|

Conservator Greg Byrne and VMFA Curator Peter Schertz examine the break between the head and neck |

||

Repositioning Caligula’s head took two days and was determined by aligning foliations in the marble of the neck on both the body and the head, comparison with other surviving full-length statues of togate figures from ancient Rome, and visual analysis of the overall composition. In the course of adjusting the head, we discovered that even very small adjustments to the head (a fraction of an inch to the left or right, a tiny bit raised or lowered) affected the overall impression the statue conveys.

The copper rod used in earlier restorations was replaced with a fiberglass rod that was fixed in place with plaster. Both the fiberglass and plaster are fully reversible, in keeping with current conservation practices and the knowledge that future curators and conservators may want to remove the head for additional study or adjustments in the alignment.

|

Portrait Statue of Emperor Gaius (“Caligula”) |

The newly restored portrait statue of Caligula will go on public view at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts by January 2014.

![]()