print version

print versionLENA MOSES-SCHMITT

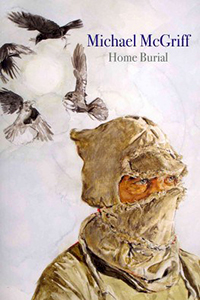

Review | Home Burial, by Michael McGriff

Copper Canyon, 2012

|

|

In a scene from The Sacrifice, by Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, a possible nuclear war descends upon Europe: the camera zooms in on a pitcher of milk teetering on its shelf as loud jets approach overhead, and the jar finally spills, shattering across the floor as the viewer hears the planes roar right over the rooftop. “I want Tarkovsky / to show them the apocalypse / in a pitcher of milk,” Michael McGriff writes of land surveyors scoping out his property in “Pipeline,” a poem from his austere yet lyric second collection, Home Burial.

His bold declaration embodies one of Home Burial’s aims—to depict the toll of some apocalypse on the smallest and seemingly most mundane domestic objects. We don’t see the precise cause of this destruction, but rather its effects, which McGriff illustrates with eerie and spectacular imagery

The poems here portray a rural Oregonian landscape riddled with barbed wire, burned-down farmhouses, footlockers of dynamite, dark bodies of water, and twisting smoke. An old Ford wastes away at the bottom of the river. A group of men gathers around a fire, “discussing what they’ll buy / with the checkbook they found / in an abandoned tract house.” The speaker’s father buys a bear’s gallbladder—“hacked out and put on ice / in California”—and “lets it warm on a tin sheet / above his Buick’s engine block” before crushing it into powder and “spoon[ing] it / into the mouth of a child.”

An entire collection of such poems could easily come to feel overwhelming or monotonous in tone or content, but Home Burial subtly demonstrates how strength and hope endure in the face of desolation. To this end, McGriff portrays the environment with remarkable balance and nuance: his subjects, as well as his carefully controlled language, successfully navigate the competing impulses of nostalgia for his community and despair over its neglect and slow ruin.

“I’ve tried to keep the landscape / buried in my chest, in its teak box,” begins the opening poem, “Kissing Hitler”; and with these lines, McGriff immediately evokes the implications of the collection’s title, not least those found in Robert Frost’s poem of the same name. He also sets the stage for the dueling desires to suppress one’s own history and to constantly revisit it; to keep it close, if only to dig it up again and again.

Indeed, this careful dance also echoes the tensions in Frost’s own “Home Burial”: After the wife has watched from a window as her husband buries their child, the couple argue precariously on the stairwell while their marriage threatens to collapse. In his essay on this poem, Randall Jarrell writes that the wife “tries to keep death and grief alive in the middle of a world intent on its own forgetful life”; one might maintain that McGriff’s collection strives to accomplish just that, if only to preserve the beauty of this world concurrently with such grief. The poems here play out these conflicts compellingly.

McGriff often instills his imagery with, if not exactly optimism, at least a sense of quiet possibility. “Symphony,” for instance, compares the sound of rain to an “orchestra tuning up, / its members taking purposeful, deep breaths,” and overlays this image with one of the speaker’s father:

When I closed my eyes

I saw my father

unstacking and restacking

an empire of baled hay,heaving his days

into the vagaries

of chaff-light.The conductor raises his arms,

whispers a quick prayer

in a foreign tongue,

then begins.

By juxtaposing these images—two kinds of work performing very different functions—“Symphony” highlights the differences and similarities between these realms. McGriff finds great beauty and humanity in manual labor—the speaker’s father, after all, reigns over an “empire” of hay. More than that, though, the poem encompasses the speaker’s intense yearning to find the connecting thread between results of hard physical labor and the production, through hard creative labor, of something lovely.

In the adjacent poems, “New Season” and “Sunday,” McGriff similarly exalts the land, while also gesturing toward its defects. His economical control of language in these sparse poems, combined with his strong imagery, introduces powerful ambiguities by allowing the reader to consider a variety of interpretations and implications. In “New Season,” McGriff’s speaker concedes that

the water

collecting in the ashtray on the porch

isn’t a lake, but it’s big enough for God

to stick his thumb in.

This passage acknowledges that holiness—or at least the possibility of holiness—graces even the most forsaken of places. However, it may also imply an absent or diminished God whose thumb would fit into an ashtray. The poem ends:

I admire the rats in the wall.

They rejoice in the night.

They call to each other

as they work.

Here, the speaker looks beyond the revulsion of hearing rats creep in the wall to praise them for their joyful industry. But because of the restraint of the poem, the implications haunt and perplex the reader— does he admire the rats for what the human inhabitants of his world cannot do themselves?

In the following poem, “Sunday,” the speaker wishes

[he] were the proud worms

twisting out of nowhere

to writhe and thrash

as if their god had fulfilled

his promise.

The reader receives few hints as to why the speaker desires to be the worms, plural, which, here, carry more pride than humans—perhaps because, like the rats, the worms so clearly belong, as the humans do not. And, like the rats, the worms have adapted and found salvation in their surroundings, when the speaker has not. As in many poems in this book, the environment is clearly breaking down: “something horselike” stands “in the flooded pasture” along with “the smell of fence posts and barn-rot.” McGriff employs his short lines and syntax to quietly brutal effect: “My mother and her illness. / My father and his patience,” the speaker states bluntly and sufficiently. Instead of unpacking these cryptic assertions, McGriff allows their ambiguity to texture the poems, leaving his readers free to do their own heavy lifting.

Home Burial likewise obfuscates the lines between human, machine, and landscape. “I get shuffled / from one day to the next / like a tin bucket,” he writes in “Pipeline,” “passed along a fire line, / the water slopping out, / never quite reaching the barn.” Openings and exits occur often in these poems, and characters are commonly in the process of either being swallowed by the landscape or escaping their surroundings. Apple trees turn into “rows of people / standing in line for something . . . waiting patiently to enter / the open doorway / of the earth.” In “Midwinter,” a woman “walks through the pasture / and out of her body.” These porous textures contribute to the intense and conflicting desires to escape and to stay; they project both hope and lack of hope (the characters must either give themselves up to the landscape or run away) creating an illusory sense of resilience and agency.

McGriff’s longer poems especially demonstrate this need to break free, as his blurring of boundaries instills in his poems a cinematic and associative process, rife with possibility and embodying movement and flight. McGriff’s lyricism, rich in imagery and syntax, yet downplayed in line and diction, provides harmony and dissonance with the rugged environment, lending his work a necessary duality. His poems often start in one place and end in another; and, though he tends to spread one sentence over several lines or even stanzas, he keeps his line lengths short, so that the ensuing interplay between line and sentence slows the momentum, simultaneously allowing the reader to linger in this distressed place and to explore somewhere new and unexpected.

Consider “The Cow,” a long, sprawling poem in the center of the book, which begins with the poet’s persona musing, “I used to think of this creek as a river / springing from mineral caverns / of moonmilk and slime / but really it’s just a slow thread of water.” We then move to a toolshed—once “an outbuilding for a watermill”—recently cleaned out by the speaker’s grandfather right before his death. “This shed should have the smell / of seed packets and mousetraps,” the speaker laments:

The sounds of usefulness and nostalgia

should creak from its hinges,

but instead there’s nothing

but a painting the size of a dinner plate

that hangs from an eightpenny nail.

The poem then moves cinematically, much like Tarkovksy’s camera, zooming in on the painting, flushing out details, each line imbuing these features with increasingly imaginative and outlandish qualities. Though McGriff never indulges in sentimentality, he also never distances himself from the world of Home Burial: his extremely close attention to inanimate details instead encapsulates the “nostalgia” that he has just denied a few lines before:

A certain style of painting

where the wall of a building

has been lifted away

to reveal the goings-on of each room,

which, in this case, is a farmhouse

where some men and women

sit around the geometry

of a kitchen table playing pinochle,

a few of the women laughing

a feast-day kind of laughter

and one of the men, a fat one

in overalls with a quick brushstroke

for a mouth, points up

as if to say something

about death or the rain

or the reliable Nordic construction

of the rafters.A few of the children

gathered in a room off to one side

have vaguely religious faces—

they’re sitting on the floor around their weak

but dependable uncle

who plays something festive

on the piano.

Before too long, McGriff’s eye settles on a cow standing in the pasture outside the farmhouse in the painting, and makes it the pivotal image for the rest of the poem, eventually conflating the speaker’s notion of himself with the cow:

This is the cow

that dies in me every night,

the one that doesn’t sleep

standing up, or sleep at all

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The cow in me has long admired

the story the night tells itself,

the one with rifle shots and laughter,

gravel roads crunching under pickups

with their engines and lights cut

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The cow in me never makes it past

the edge of the painting—

By the end, the speaker has so merged into the painting that we almost forget there was a painting at all, with boxed-in borders and four corners. The effect of this associative movement surprises—acting as an escape, it momentarily jolts the reader out of the poem’s literal setting and into an imaginative mindscape. McGriff’s lyric riffs suggest limitless possibilities for the inhabitants of this land.

Home Burial’s permeable atmosphere occasionally mythologizes the land or the characters in these poems. In “My Family History as Explained by the South Fork of the River,” McGriff writes:

My grandfather says

he stepped out of his dream

the same day my grandmother did.

In this way they entered the world.If you put your ear to his chest

you’d hear something so absolute

that you’d leave for the river

enter the salmon run

and disappear through the keyhole

at the river bottom.

Beyond the voice or content, such mythmaking touches the reader with its tender impulse to account for an already diminished homeland. By making his characters more than merely mortal, McGriff’s poems restore and breathe new life into this lost land.

But above all, the repeated merging of landscape, human, and machine drives home the poet’s implication that we cannot separate ourselves from the places and things that shaped us. Home Burial, thankfully, refrains from predictable and simplistic commentary on the decline of this way of life—but the poet’s subtle evocation of the underlying questions of cause and cure create a poetic atmosphere that, however grim, makes the reader reluctant to leave. ![]()