print preview

print previewback CRAIG BEAVEN

Review | Signaletics, by Emilia Phillips

University of Akron Press, 2013

|

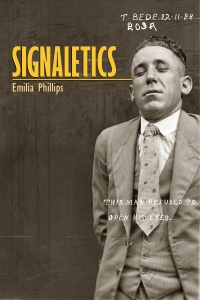

On a first encounter, Emilia Phillips’s Signaletics could easily overwhelm the reader with the sheer volume of source material and information embedded in the book. Beginning with the cover (a 1928 Australian mug shot) to the title Signaletics (referring to a book by Alphonse Bertillon, the nineteenth-century French criminologist and developer of Bertillonage, the system of anthropometric classification widely used to identify criminals until fingerprinting eventually proved superior), Signaletics invites the reader to encounter other books, other authors, other texts. From the notes at the end, I count references to sixteen different authors, not including the allusions to or uses of songs, scientific texts or concepts, four works of art, Morse code, and dental practices, and I’m not entirely sure that these notes are truly comprehensive of everything that appears in the book.

The incredible amount of information testifies to the imagination and vision of the author. Phillips must have a restless curiosity and a fierce intellect to have cast her poetic gaze so widely, and to have made lyric use out of such disparate materials. As with any excellent poetry, these adventures, characters, stories, and songs all become a part of the self, become amalgamated into the author’s own persona.

Unlike many young poets, Phillips avoids self-absorption and exclusively personal history. Rather, the varied source materials act as a mirror: the frustration of a male Capuchin monkey’s inability to find his wife in the phonograph recording of her voice merges with a man’s driving “a screw- / driver into the cell repeating, I’m sorry. // Your call cannot be completed / as dialed.” A museum visit to Messerschmidt’s grotesque “character heads” takes Phillips’s speaker, by way of a meditation on English words derived from Arabic, to her father’s accidental but bizarre gunshot injury—“You see,” she reports calmly, “he thought someone was / trailing him, and maybe they were”—and from there to a way back into herself, through the oddities of the outside world: “And if, now, I think of Job, / saying, I have said to corruption, Thou art my father, // where now is my hope?” At the end, the book resembles a strange museum or a really eccentric antique shop. One senses that Phillips has needed to explore these strange places, has found the materials that will answer her personal questions, and has come out on the other side of a long quest with finely wrought creations—renderings—of what she found.

Perhaps the best of these poems, the six poems each titled or subtitled “Latent Print,” best exemplify how Phillips lets the world into her work. In the first of these, “Vanitas (Latent Print),” a father tries, unsuccessfully, to take fingerprints of his dying son. “The nurse’s ink would not do: so heavy it flooded / the ridges to smudge the white paper . . . ” Ultimately, the nurse brings “an aluminum can to which we pressed the hands // for prints my father, unfathered, would lift later with dust.” In another from this series, Thomas Eakins’s photographic studies give way to fatherly advice: “If you’re ever kidnapped, bite / the car door . . . / I can find you / that way.” These concepts of “imprinting,” of making a record and keeping it forever, of leaving a mark and of being in the world, all coalesce in this brilliant sequence—the perfect image to convey Phillips’s thesis.

This thesis, as suggested by the book’s title and the sequence that follows it, concerns meaning-making and discovery—how a human reads the world around her and makes sense of it. Alphonse Bertillon makes many appearances in the book, as do automaton-makers and primate-speech researcher R.L. Garner, people who have tasked themselves—and in some instances driven themselves mad with a desire—to “know” the world around them, to translate it and unpack it, to lay it completely bare. Phillips herself, another explorer in this cadre, knows the only resolution we find lies in the journey, the desire. As such, the poet becomes a curator of others who have gone before her—especially, here, a father figure, perhaps always the same father, although he appears at times as a criminal detective and at others as a US soldier in Iraq. But in all cases he seeks to experience and touch a permanent truth or center that will set him free.

“Cross Section” begins with a ghostly speaker lowering herself into a cold bath to break a fever; from there the poet’s consciousness travels to “B.”—a recently cremated woman “in the chamber where a magnet // will skim her ashes for screws, bone / fasteners, & crowns.” “A pacemaker explodes in the fired / chamber,” the speaker muses, picturing the heart machine in the crematorium’s machine, together destroying a body and rendering it to its essence. From this icy bathtub reverie, she finds herself in an airport, gazing at a magazine diagram of Al-Jazari’s famous elephant water clock, which features a device that “continually fills, becoming heavy / with each hour.”

In a similar and equally revealing meditation, “Skin Mags,” Phillips considers the women in a cache of vintage adult magazines, “unchanged by . . . / erosion, meltwater, the giving up // & letting in . . . ” These bodies—their renderings—have survived being “stuffed in floorboard, attic, basement, // a strongbox,” and their real-life counterparts have now aged out of these photos (“All of them now // old enough to be my grandmother”). Phillips observes that, “We snare / our ghosts for historical consequence,” the models a signifier of human need to make permanent, to feel desire, our innate human longing to hold onto something that will inevitably age and decay.

In these expertly wrought, complex lyric poems, Phillips engages the ancient conundrum of all lyric poetry and leads us through a fascinating world of seekers. Desire, permanence, the self versus the world, history and the lived moment, records and recording, the poetic gesture as another historical text—all of it comes to us through a variety of baubles and narratives, toys and photographs. We take the journey with her and find treasure for our efforts and Phillips’s. ![]()

![]()

Emilia Phillips is the author of Signaletics (University of Akron Press, 2013) and two chapbooks. Her poems appear in Agni, The Kenyon Review, Poetry, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, U.S. Poets in Mexico, and Vermont Studio Center as well as the 2012 Poetry Prize from The Journal and second place in Narrative’s 2012 30 Below Contest.