print preview

print previewback ROSS LOSAPIO

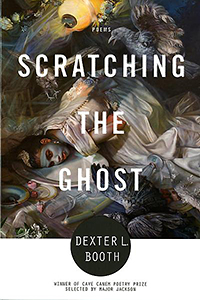

Review | Scratching the Ghost, by Dexter L. Booth

Graywolf Press, 2013

|

Dexter L. Booth’s poetry comes face-to-face with the shocking and sickening while reaching for the sublime, a seam of pain running through its core. His writing confronts the past with the same unflinching tenacity of a man obsessively picking at a wound. The poetry in Scratching the Ghost seeks out what lies beneath the scars, searches for meaning within the hurt. “Dear pomegranate,” he writes in “Under the Weather,” “dear wild iris and seed, I will do things differently the first time— / again.” Booth’s poetry plunges into the flesh and draws gleaming, blood-red pearls up from the past, turning them over and examining all with fresh eyes.

Booth’s reverie often shifts into focus through a haze of fog or cloud. “I’m still not sure what it means,” he recalls of notes jotted on a map in the dark in “Letter to a Friend.” “One night I dreamt of driving in a fog so thick I couldn’t see my hands. I kept passing my house. No matter what exit I took there it was.” The words and diagrams elude the speaker, though they originate within him. He pushes them to the periphery, at least initially, but they loom and insist as the ethereal house of his dream does. The fog seems to menace and occlude, but it does not do so absolutely. In fact, it adopts a different aspect in “Prayer at 3 a.m.”:

I’ve seen this from you both: cartwheels through the field

at dawn, toes popping above the corn stalks like fleas

over the heads of lepers. Your scarecrow reminds meof Jesus, his guilt confused for fear.

The sun doesn’t know; the fog lifts

everything in praise.

Clarity rarely offers the comfort that readers, grown accustomed to light and song as agents of praise, expect. Washing a grown man’s pants in the sink in the middle of the night, the mess that it implies, reflects a bleak, numbing lucidity. The deeper revelations in Scratching the Ghost buoy up on roiling clouds.

The lens through which these poems operate focuses, glances away, and focuses again, parsing out information to devastating effect. The collection’s title poem opens, “Tonight, you are bald, your head dented / like the moon.” The ghost’s ominous presence silently stoops over these lines, posing persistent, nagging questions in the reader’s mind. What presence haunts this poem? Who is haunted? As the poem progresses, the scene slowly clears:

the clouds offer their somber news

through cracks in the blinds.

Their splayed fingers are dancing

in tune to Kenny G. The stub of your left leg dangles

as I hold you up, my hands under your arms

like a child. You are complaining about the itch,

the burn

Like glimpses of the horizon through a passing storm, an elderly woman with an amputated leg—a truly phantom limb—hovers into view and reveals the nature of the apparition. Trapped within the confines of her own body, the poem’s subject becomes her own ghost, a realization that strikes even harder for its postponement. Throughout Scratching the Ghost, Booth demonstrates a mastery of delayed gratification.

Followed by persistent and often unsettling memories, Booth’s speaker naturally seeks meaning within them. Surrounded by death and violence, out of necessity he looks inwardly for redemption. If we return to “Under the Weather,” we notice that a rare moment of tranquility unfolds:

A child once told me the sun is the deadliest animal—

violent, never blinking. On Sundays

I sit on this mountain with a bottle of water and a book—

any book—not reading, jotting balloons in the margins.

Perched alone on his peak under the sun, the speaker strikes an ascetic pose. One might expect, were this a just universe, that deadly animal sun to open up and dispense words of wisdom or compassion. Instead, as the collection advances, the speaker becomes his own Christ-figure. “To be truthful,” he admits in “Letter of Self-Abduction,” “I crawled on my belly until I was twenty. / I broke my nose violently kissing feet.” He exhibits dramatic, but self-contained subservience in these lines, which soon grows beyond mortal limits:

What else could I have been

looking for but passage? For the lips to probe for something more

to witness than the body I praise, even as it fails?

I smell what is sweet now, and softly knotted

in surrender. Still, I wished these thorns, crooked and stained,

I wished this flayed skin above the brow to accept

their committed bending.

Whether it is his mother’s death or the abuse meted out by his “sister’s father,” deep but sporadic and irreconcilable pain dogs his heels. However, he controls this new suffering—simultaneously burden and gift—and imbues it with an underlying logic.

Even as Christ sacrificed his mortal body for humanity’s salvation, Booth’s writing disassociates the body from its owner. In the most virtuous of cases, this is enacted as a noble gift. In more gruesome scenarios the figures populating Scratching the Ghost treat the mortal coil as little more than an expendable commodity, as in “The Body” where the speaker recounts his first experience touching a woman’s breast: “They ran when she began coughing / up blood. I opened her shirt, / pushed on her nipple like an alarm.” Horrifying alone, the act takes on a more troubling context as it echoes the slaughtered hog that opens the piece:

It was cold and raining, I remember

the steam and the knife and the squeal and howthey all left the body like a ghost.

They lasted and lasted and the body shook

in your hands. I was

told this is sex my friend,be still.

Booth takes pains to logically and instinctually separate soul and body, making it clear that the latter is of little consequence. “You are just a box,” opens “Poem for my Body.” “I knock against / you like a fly in a jar.” The body is a nuisance, a cage entrapping the speaker’s true nature. The world sees him, the lines imply, without seeing him. This phenomenon extends beyond the self and into the world. In the preceding poem, he reflects on a popular fifth-grade class project: designing an apparatus that will transport an egg safely to the ground from a designated height. Poised atop a fire truck’s extended bucket, the speaker does not follow the trajectory of his Jell-O-packed egg, but rather reflects that “the city looked like a map of a city.” This world is merely its seeming, an advantageous viewpoint when compartmentalizing and justifying one’s own suffering.

Despite the body’s relative insignificance, Booth values one component well above the others. Even as “Self-Elegy as River” pays tribute to the death of the self, it raises the tongue to God-like eminence:

Now that tongue rolls

behind the teeth.

The only thing you could ever keep to yourself.

Little wrecking ball.

Tiny muscle of demise.

The words cascade down the page, as if pushed down a flight of stairs or collapsing under their own weight. The poetry of Scratching the Ghost seeks control and, ultimately, finds it in the tongue’s brawn, in the breath’s current propelling the words forth. “He has the will to pray,” Booth states in “Ars Poetica with Silence and Movement,” “believes there is still power in words—he must.” It is a difficult task to fashion oneself into one’s own savior, evinced by the series’ form becoming more sporadic. The body buckles under the pressure, but the word survives. ![]()

![]()

Dexter L. Booth won the 2012 Cave Canem Poetry Prize for his debut collection, Scratching the Ghost (Graywolf Press, 2013). His poems have appeared in Blackbird, Virginia Quarterly Review, and Grist, among others. Booth teaches poetry and English composition at Arizona State University.