print preview

print previewback CHELSEA GILLENWATER

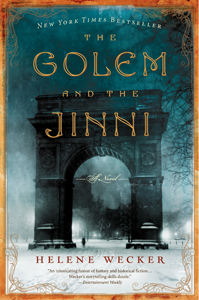

Review | The Golem and the Jinni, by Helene Wecker

HarperCollins, 2013

|

“We’re our natures, you and I,” says the Golem to the Jinni, and with that, Helene Wecker cracks open the principal question of her debut novel: What does it mean to change our nature? Various elemental forces propel Wecker’s fantastic beings—the Jinni, a wandering, restive spirit made of fire who shirks responsibility for his actions; the Golem, a clay creation meant to operate without free will, who longs for stability and kindness. Although they can conjure flame, run faster than trains, and inhabit human minds, their mortal flaws and limitations utterly define them. As the two try to adapt to the temporal world of nineteenth century America, they contend with the question of whether they should accept those natures—destructive tendencies and all—or whether they can find something worth emulating in the fragile, fallible humans they encounter every day.

The Golem and the Jinni relies on a kind of slow, reflective storytelling, but the novel always crackles with energy that Wecker taps out evenly, building to an electrifying conclusion that pulls the main players into collision. Wecker’s rich mythology, culled from the myriad real-world legends of golems and jinn, establishes an effective groundwork that immerses readers in her world within the first few pages. We begin with Chava, a golem-wife custom-made for her master (who dies before their life together can begin), as she winds up alone on the shores of Manhattan. She soon encounters a kindly rabbi who—having studied some of the ancient, forbidden texts of his order—recognizes her as a creature of clay. With his help, Chava acclimates to the human world and learns to disguise the telling signs of her magical origins: her terrifying strength, her ability to instinctively detect others’ thoughts and desires, and her utterly selfless compulsions. In the same city, a Syrian blacksmith named Arbeely unwittingly releases a proud, reckless jinni from a flask. Held captive for hundreds of years, the Jinni struggles to adjust to his new human form and retrace his memories to discover what led to his imprisonment. Arbeely offers the Jinni a job and names him Ahmad, but Ahmad strains against the seemingly endless limitations of human life. The novel flips primarily between these two creatures’ perspectives, though plenty of fascinating human characters round out the cast, their stories becoming increasingly intertwined.

Wecker drops her characters into a turn-of-the-century New York City that feels as epic and sprawling as any fantasy universe. Wecker’s descriptive prose makes the urban backdrop becomes a chaotic, teeming landscape full of wonder and mystery. Even mundane activities, like taking a ride on the Elevated (Manhattan’s early transportation system), take on a grand sense of scale and adventure:

It was a wild, giddy ride. The noise was deafening, a rattle and screech that penetrated his entire body. Sparks from the track leapt past, blown by a violent wind. Lamp-lit windows flashed by in bright, elongated squares. At Fifty-ninth Street he jumped out from between the cars, his body still shaking.

Wecker achieves an extraordinary balance between our world and the novel’s magical elements, and the realistic setting opens the door for these characters to grapple with the question of what it means to be human within the boundaries of our familiar, flawed society.

Wecker sets her novel in an America that seems rife with possibility, and that choice allows her characters to examine some of the United States’ more idealistic principles from a fresh perspective. Even a days-old Chava notes that the Statue of Liberty, towering and severe, is “loved and respected” by the weary immigrants at her side. The statue at first reminds Chava of a giant golem, Liberty’s gaze turned toward the incoming refugees with the same selfless, single-minded devotion that drives Chava to help everyone she can. That spirit of achievable goodwill creates a pervasive sense of intercultural collaboration that allows Wecker to weave varying mythologies together almost seamlessly—the Middle Eastern stories of elemental jinn alongside the Yiddish blood rituals involved in the creation of clay golems. The effusion of cultures, religions, and eventually magical beings colors Wecker’s narrative with endlessly colliding perspectives, and as more and more characters cross paths, those colors grow even richer. Wecker explores the concept of the American melting pot to its fullest extent here, and the lines between human and creature continue to blur as Ahmad and Chava find themselves embroiled in the everyday flurry of human drama.

Wecker devotes great attention to shaping the distinct communities of an immigrant city, creating a Manhattan that functions as “a miniature Babel,” a true monument to multiculturalism, and the Golem and the Jinni interpret their multifaceted city in vastly different ways. Both instinctively understand all human language, so the boundaries that hem in New York’s disparate populations do not apply to them. They can experience a variety of perspectives easily, shifting between classes and cultures that might ordinarily never overlap. At one point, Ahmad strikes up a passionate affair with a young socialite, dismissing the city’s prevailing adherence to “proper” courtship as ridiculous. As he explains to the Golem, “It should be easy. [Humans] are the ones who complicate it beyond reason.” In matters of sex, religion, and labor, Ahmad questions the limitless restrictions mankind seems to place upon itself, and he sees nothing but opportunity in the city’s plurality, a chance to experience as much of the world as possible, whenever he chooses. Chava, too, hears the cacophonous thoughts of thousands of New York’s immigrants, no matter their background, but their frantic desires feel “like many small hands, grabbing at me.” Chava cannot help but see others’ plights as responsibilities she must assume. She witnesses the degrading effects of poverty firsthand in the mind of a young boy stealing his dinner or in her coworker’s desperation to hold a job before her pregnancy forces her into the streets. Chava gravitates toward people working to stem the tide of suffering, such as the rabbi’s nephew, Michael Levy, who runs a safe house for new Jewish immigrants. These encounters with humans, both meaningful and fleeting, anchor Chava and Ahmad in the overwhelming swell of the city.

Although in many ways Ahmad and Chava find New York a gentler place than they expected, they remain within the city long enough to discover its darker conflicts. Throughout the novel, the nature of the city kaleidoscopes in tandem with the characters’ emotional arcs, and the landscape assumes different hues and tones as the story progresses—from the lively bustle of Central Park or Little Syria to a more mechanical wasteland utterly devoid of will:

The wooden rides seemed skeletal, like the remains of huge abandoned beasts. . . . [The Jinni] boarded the car and rode south, watching as the trolley filled and emptied, delivering workers to the factories and printing presses, the sweatshops and the docklands. The more he rode the trolleys and trains of New York, the more they seemed to form a giant, malevolent bellows, inhaling defenseless passengers from platforms and street corners and blowing them out again elsewhere.

At her characters’ lowest points, Wecker reveals to us the great paradox of late-nineteenth-century New York City: how the promise of freedom sometimes rings hollow at every level, from the tedious churn of industry to the stifling restrictions of Manhattan’s high society.

In his interactions with humans, Ahmad sees dim reflections of his own imprisonment, entire lives ground away beneath the oppressive weight of the city. Though no longer confined to a cramped flask, he begins to think that he would rather remain trapped than live out a seemingly purposeless existence in New York. Even Chava, who often finds herself desiring the simpler, more structured life of serving a living master, chafes against the limitations of mortal bodies. Although she does not need to sleep or eat, she must go through the motions in order to avoid drawing unnecessary attention to herself and to keep her more destructive propensities in check. In an effort to give herself some security, she eventually proposes marriage to her friend, Michael Levy, but she wastes away in an effort to make herself more human for him: “The long stretches of lying next to him in bed, remembering to breathe in and out. The excuses for her sleeplessness, her cool skin. Would he notice that her hair never grew? Or, God forbid, that she had no heartbeat?” She begins to “wonder whether she still had a will of her own.” Such inventive leaps in mythology give Wecker an opportunity to explore feminist ideas through the lens of a character who wonders how her life would change “if she’d been born instead of made.”

The restlessness that plagues both characters slowly begins to stifle their identities, and the Golem and the Jinni eventually find it best to isolate themselves. But Wecker stresses a pervading sense of interconnectedness, a concept made explicit through her mythology—the boundaries between individuals shift and overlap, as the two characters can share thoughts, dreams, and even entire lifetimes. These wavering identities occasionally lead to catastrophic effects for the humans touched by supernatural forces—a girl Ahmad encounters before his imprisonment loses her sanity after he enters her dreams, and from then on, she sees the human faces before her as “sepulchral, the eyes like dark hollows.” Likewise, the bonds Chava forms with her masters strip her of her free will and frequently drive her into cold frenzies of violence over which she has no control. Ahmad and Chava want to distance themselves from their companions, but the need for interaction proves inescapable for everyone in the novel. In Wecker’s world every relationship produces a lasting impact, and as we move toward the novel’s conclusion, those interpersonal connections become just as powerful as the magical spells that bind the Golem and the Jinni into their forms. Chava divines Ahmad’s actions simply through the fact of their emotional intimacy: “She didn’t need forbidden diagrams or formulae to tell her his destination. She knew; she knew him.” That bond becomes a force more powerful than any master, though Wecker reminds us that loving someone—in any capacity—can be just as devastating and cruel as enslavement.

The parallels between the Jinni and the Golem, humans and nonhumans, their past and our present all work together to create a remarkable, subtle, moving tapestry of colliding cultures and personalities. The Golem and the Jinni tackles its themes with deftness and sensitivity, all without ever losing that engaging, page-turning energy. In the end, Wecker achieves a vivid collage of characters, and their relationships form something that resembles a disordered, sprawling, ultimately uplifting family, one that has—after all—been made instead of born. ![]()

![]()

Helene Wecker is the author of the novel The Golem and the Jinni (HarperCollins, 2013), which received the 2014 Mythopoeic Award, the 2014 Harold U. Ribalow Prize, and the 2014 Cabell First Novelist Award, and was a finalist for the Nebula Award and the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel. Her fiction has appeared in Catamaran Literary Reader (2013) and Joyland (2013). Wecker holds an MFA in fiction from Columbia University.