print preview

print previewback ROSS LOSAPIO

Review | Our House Was on Fire, by Laura Van

Prooyen

Ashland Poetry Press, 2015

|

“Listen, then,” begins Laura Van Prooyen’s Our House Was on Fire. “Listen, then” opens the poet’s second collection not merely in medias res, but in the middle of an argument or plea. An off-balance and ever-shifting relationship between the speaker and the reader issues from these two words; the former seeking something—permission? forgiveness? acceptance, perhaps?—from the latter. As the collection progresses, the speaker slowly brings the lives of her children and husband into perspective, and a melange of guilt, joy, and pride emerges. She acknowledges the past but also imagines alternate paths she may have taken in life. Throughout Our House Was on Fire, the reader enjoys an honest and admirably vulnerable account of a mother, wife, and woman discovering, defining, and defying these roles.

A series of “doubling back” gestures populates Van Prooyen’s text, in which the speaker immediately negates or revises something just said. The poem “Between What Is Possible and What Is Desired,” for example, creates an idyllic park scene, its speaker musing by a lagoon filled with geese and willows. She asserts, “your appearance confirms this is not a dream.” Just a few lines later, the speaker changes tack, stating, “Your appearance confirms this is a dream.” At times, these instances signal reality coming to bear; however, these movements serve other purposes, as well, and offer the reader beautiful and complex moments of untangling. “Revision” begins with the line “Understand, this is a story”:

A convertible speeds past with the top down.

Wait. Back up. The neighbor invites mefor a ride on his bike. I think yes. I say no.

Our daughters hear me and laugh. In this story,we have no daughters. You are a stranger

and I am the girl. This is the beginning.

In this case, the doubling back spins a fantasy, allowing the speaker to edit history to omit her husband and children, if only temporarily: an indulgent, somewhat selfish, but utterly empathetic gesture. As we continue, the family dynamic and the stakes at play slowly distinguish themselves and the reader becomes something more than witness or interloper: a confidant.

Van Prooyen’s “This Child” is Brothers Grimm-like in its exploration of a daughter’s dream of chopping up and eating her mother. Racked with guilt, the child confesses her imagined crime to her mother, and the two comfort each other. Even so, the poem culminates with the lines, “we both know / where the knives are,” implying that mother and daughter, though they love each other, possess just the right tools to wound. Though unsettling, the ultimate inability to protect this child is the mother’s true source of terror. A fascinating bridge occurs between the poems “Happiness” and “How Quickly Nothing Is Familiar,” demonstrating the poet’s deft hand at thematic framing. In “Happiness,” the speaker reflects upon a particular foolhardy episode from her childhood in which she jumps on the back of a stranger’s motorcycle,

never thinking

he could drive me to the cornfieldand leave me there when he was through.

It doesn’t really matter that I ended upwith only a tailpipe burn.

A frighteningly similar scenario plays out on the opposite page as the speaker’s daughter runs off into the woods, “a bloom // in a tunnel at the bend where the man / disappears. Before I think to say no.” Many parents hope to see a reflection of themselves in their offspring, but that image distorts and disturbs as well.

Van Prooyen wisely leaves the reader to puzzle out meaning in the wide emotional gulf her speaker carves out. Dual impulses—to either damn or praise—war on the pages of Our House Was on Fire until the poet, such as in “Undoing Her Hair,” parses out a crucial piece of information

that made the mother think

back to the first fever

and spinal tap, to her child

curled up, delirious

at the onset of disease

and know the more

the body fails, the more

the girl speaks of what

the mother cannot see

The speaker’s proverbial trials as a mother whose daughter grows up to be just like her seem euphoric compared to this new, unfamiliar and unknowable terror. What is a parent to do when, as in “On the Discovery Channel,” her child laments “the stupid, stupid mothers” who let their caribou calves wash away? How to explain disease’s unrelenting river?

“This is how my daughter thinks about death, a small ceremony / followed by the hope of swift replacement,” the speaker reflects in “Two Novembers.” By the poem’s end, however, the daughter has emerged from a Thanksgiving with her ailing grandfather and the death of her cat, and we witness a distinct maturity of thought: “And this is how my daughter thinks about death. They will shave / a patch off the cat. She’ll cradle our pet in a towel on her lap and watch / its face when the needle goes in, because she wants to see how it looks.” Curiosity and understanding gradually supplant the fear and anger with which she struck out previously. This transformation occurs to the extent that, under the right circumstances, a complete role reversal takes place, as in “The Sweeping Inside”:

When I sat in troublesome silence,

she thought to do a flip

on the swing would bring

some cheer. When it didn’t

we made our way to the store,

where I scan rows of cans,

squeezing her hand that holds me here.

Daughter becomes caretaker for the mother, who now might disappear at any moment. The astounding symbiotic relationship between parent and child completes its circuit.

Laura Van Prooyen’s poem “One Particular Peach” begins, “As if this bowl / weren’t filled with peaches,” musing on that implied richness. In many ways, this bowl of peaches characterizes Our House Was on Fire, each poem promising an experience that the reader can sink his or her teeth into and then must carefully chew and digest. Unlike those peaches, though, Van Prooyen offers us an uncategorical selection, not only the sweetness of joy, but also the bitter notion of regret, the airy notes of fantasy, and sour pits of contrition. ![]()

![]()

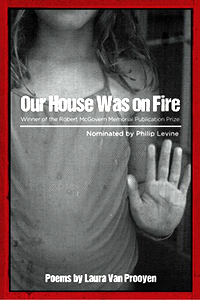

Laura Van Prooyen’s second collection of poems, Our House Was on Fire (Ashland Poetry Press, 2015), won the 2014 Robert McGovern Memorial Publication Prize, nominated by Philip Levine. Van Prooyen teaches creative writing at Henry Ford Academy: Alameda School for Art + Design.