print preview

print previewback LAURA VAN PROOYEN

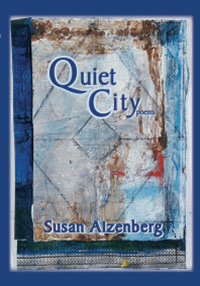

Review | Quiet City, by Susan Aizenberg

BkMk Press, 2015

|

“This evening rough winds blow the surface of the river. / The starlings and purple martins have flown / to quieter skies,” declare the opening lines in Quiet City, Susan Aizenberg’s second full-length collection of poems. Like the image of water troubled by wind, Quiet City flows with meditative poems and lyrical moments rippled by tension. Divided into three sections, the book begins with the speaker as astute observer, delving into complex familial relationships. Section II examines perception and influence as it relates to identity and includes two of Aizenberg’s collaborative translations of the Chinese poet LuYe, while Section III addresses history, confinement, and aging. The book, when considered as a whole, impressively weaves together recurring concerns about gender, circumstance, and power. These direct and often haunting poems meld memory with imagination, revealing relationships that interrogate the idea of control.

A series of unsettling details in Section I highlights the way family members can both wound and be wounded. In deft and tightly controlled couplets, “Via Negativa” tells the story of the Quakers who created a prison that enforced upon its charges strict quiet and isolation; the poem then introduces the speaker’s father who “believed in the power / of true regret” and imposed upon her mother “weeks / of silence” while remaining “cheery” with his children. At night, the speaker would hear her mother through the walls pleading with her father to talk, but he wouldn’t respond. The mother was confined in silence, where even her husband’s steps:

when he left for work in the morning

were soft as the muffled treadof the Eastern State guards

in their felt slippers, the wheelsof their carts wrapped

in cotton wool. . . .

This chilling comparison of the father to penitentiary guards speaks to the mother’s futile situation and the maddening desperation that withholding can create. And while the father’s passive-aggressive move was meant to hurt the mother, the children by proxy endured the sting. This is not to say that the father was all villain. Family life is complicated, and Aizenberg skillfully shifts the lens between poems to offer multiple viewpoints. We discover in “Mornings” a sympathetic portrait of a father disgruntled with his job, who would take predawn walks to the diner for his own moment of peace. In “I-80,” one of the collection’s most honest and moving poems, we find the speaker as a mother with a troubled teenage son. She recalls an afternoon where she refused to pick him up from a bar, and he had to walk twenty miles along a frozen highway. She intones:

That was the year of bail bonds

and rehab, the orange jumpsuitsof County Correction, weeks I shopped

for pounds of macaroni and cheeseuntil he said it made him sick—

and wasn’t that what I’d intended?—

It’s the sharp edge of understanding that hurts. It’s the speaker’s recognition that love exists between child and parent, between husband and wife, as a prickly mix of pain, vulnerability, and culpability.

Section II opens by turning the tables on oppression and claiming it as the birth-source of the creative mind. In “Toward an Autobiography of My Imagination,” the speaker declares that her inventive powers were “born the day the babysitter / locked me in her storeroom for toppling / her boy’s tower of alphabet blocks.” The personified imagination becomes the speaker’s companion and guides her through Miami, Brooklyn, and episodes with her father. We sense, in this section of the book, that if the speaker can live in the presence of the imagination, it will shield her from difficult memories such as those in “Evening” where her father berates her as a child, calling her “stupid” while she does homework. Or the imagination will help her recognize lies, like those her mother discovers about her father’s military life in “The Unloved Beautiful.” But even imagination cannot protect us from memory loss and aging, as the speaker observes at a nursing home, watching people “who doze / and nod, tremulous as dandelion puffs, // on the stalks of their necks,” a comparison that affirms Aizenberg’s gift for evocative imagery.

The scope of the collection expands to include political and natural forces of power in Section III. The poems range in subject from the Dust Bowl to the internal workings of a jail to a photographer who documented the “vanished Jews of Warsaw, 1936.” Ghostly traces of what had been populate this section of the book, where we find the father’s writing “elegant as typescript, before his stroke” and the grim transformation of Nazi-era Berlin, where:

the corner bakery’s window display

changed from dark loaves and sweet cakes

to what looked like antique radio

antennas—devices for measuring skulls

Mixing what had been with what is, the book’s final poem, “Everything That Rises,” juxtaposes beauty and brokenness, emphasizing the speaker’s complex, multilayered world. Aizenberg draws in the reader, employing an inclusive second-person point of view: “You’ve made love with your husband . . . // You don’t want to know just blocks from here / three tweakers are cutting up a comrade they believe // holds out on them.” The poem spins through place and time, landing with the speaker’s aging mother, who calls “from her pink condo beside the ocean” and “swears” the speaker’s “dead father was there.”

If Quiet City begins with a struggle against gendered roles and other forces of control, the book ends in a sort of release. As the mother stands in her condo, her daughter, miles away, imagines her to be in “her faded / nightgown, the sultry air troubling the curtains.” Unlike the “rough winds” that rippled the surface of the river at the book’s start, the air has a breezy, balmy vibe by the end, though it still troubles. Quiet City is a solid, satisfying collection that offers a complicated view of power and intimacy that exists in spite of vast distances, like the daughter who imagines her mother in a condo far away, “phone in hand, watching / the wide gulf.” ![]()

Susan Aizenberg is the author of Quiet City (BkMk Press, 2015), Muse (Southern Illinois University Press, 2002), and a chapbook-length collection of poems, Peru (Graywolf Press, 1997). She is the coeditor of The Extraordinary Tide: New Poetry by American Women (Columbia UP, 2001). Her poems have appeared in AGNI, Chelsea, The Journal, Midwest Quarterly Review, Prairie Schooner, and Spillway, among others. She is a professor of creative writing and English at Creighton University.