|

MARK HARRIS | On

Aspects of the Avant-garde

|

Thanks

very much, Richard, and thank you all for coming. I'm sorry it's

going to be uncomfortable for many of you. I'll try to speak up,

and I'm reading something, so it should go quickly. I'm not showing

too much of my work—about four slides of my work and a video

that I made a year ago, which is just going to run, while I talk,

behind me. Because it's quite a theoretical text, I thought it

might help to have something else going on. So if you get bored

with this, you can look at that, or if that's not interesting,

you can come back to me.

I always feel very nervous about lectures,

so I really try to get myself in the right frame of mind by getting

dressed up and having a drink beforehand. It's a talk on theories

of the avant-garde, aspects of the avant-garde, with an emphasis

on intoxication. I hope that it doesn't go to my head too much.

But I'll put this video on [Flies, 2003], and maybe we

could have the lights . . .

|

|

Mark Harris, Flies, 2003.

|

October,

definitely the month of iconoclasm. After Richard Roth's talk,

here is yet another one that proposes there might be something

to gain from

reconsidering

the role of the avant-garde. And in the tradition of VCU responses,

I welcome flyposting in

the school tomorrow,

but

I should

inform

you that my penis is already very small, which doesn't leave

you much opportunity for further reductions. I don't have any secure

answers, really, to the question of the avant-garde, just a few

propositions. Perhaps

you'll

be able to help me out along the way. These are really propositions

rather than assertions or statements, and any feedback would be

valuable. In a way, in a sense, this paper would be better if it

was given in a workshop situation for discussion.

Here we go.

In the background

to these thoughts also are speculations about whether what

goes

on in any

art school

really constitutes

an education, whatever we decide that ought to be. I don't want

to be misunderstood in this point, so I should clarify just one

thing. Although I have some doubts about current art school education,

I am certain

that the questioning that goes on now in most schools is more

productive than the kind of academic training I received at Edinburgh

College

of Art, where we rehearsed life drawing and life painting, still

life and landscape, four out of five weekdays. We were really

student casualties of an administrative and academic failure to

address

the implications of any twentieth-century artistic innovation,

let alone respond to the intense questioning of the value of

culture going on in Britain during the 1970s. Learning to draw

and paint

in that way is really to learn nothing.

And so to the avant-garde, the term which qualifies

much of what we understand as significant twentieth-century art

and whose legacy of innovation and questioning still informs the

remit for significant student work. I wonder what

conceptions you have of this phenomenon. You might consider for

a moment what the

term avant-garde means to you. Maybe you have some embarrassing

recollection, like a teenage crush you'd rather forget about;

as in, "Yeah, the avant-garde, wasn't it weird that

that was so important once?" Or maybe you use it in a throwaway

manner, where its meaning is just an empty shell, as in, "Hey,

this is so avant-garde." Or maybe, maybe something ambitious

with political goals in mind, as in: "By Friday, my avant-garde

work will have changed . . . the world, Richmond, whatever."

The

fact that it's easier to find a voice for the first two instances,

for

the

fading

away or empty versions, indicates how unlikely a plausible agenda

for the avant-garde has become. Its everyday usage is awkward.

We're aware, without even thinking about it, of the increasing

distance between its historical importance and its current lightweight

status, disengaged from real achievements.

I'm making a few assumptions

in this talk. They concern the avant-garde's antagonism to society

while continuing to receive its support and approval, the kind

of approach which says, "I hate you, but give me a grant,

please." This complicity with what it attacks is well known

to anyone familiar with avant-garde studies.

Because this isn't

really the time or place to go into this in much detail I'll

try to be brief. The history first.

There's no doubt that

from the start the avant-garde meant opposition, with the result

that political engagement forms the backdrop in front of which

the avant-garde has continued to perform ever since. From the

Parisian Saint-Simonists in the 1830s issues the call in the

first place for artists to form an avant-garde and propagandize

the socialist cause. This link between aesthetic and political

radicalities remains evident for the rest of that century. Without

actually calling themselves such, there are nineteenth-century

artists working oppositionally like an avant-garde. In fact,

until the 1870s the term had somewhat dilettantish connotations.

But how was their opposition expressed?

|

|

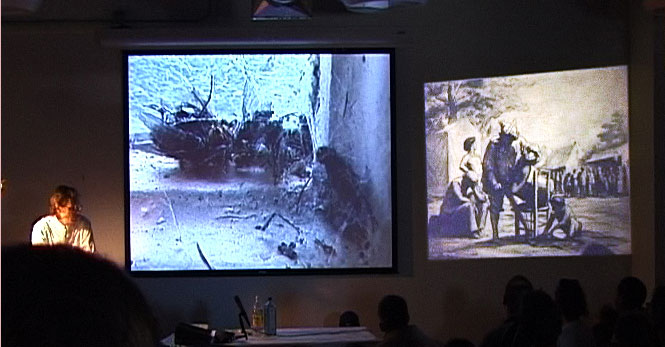

Honoré Daumier, Rue Transnonain, lithograph, 1834

|

|

How was

this opposition expressed? T. J. Clark shows how Daumier's

work [slide 1: Rue

Transnonain,

lithograph, 1834; slide 2: Saltimbanques] forms a compelling

attack on French institutions.

And here is

the work called

Murders or Massacres at Rue

Transnonain,

which was Daumier's representation

of the murders by government troops on innocent occupants of

a house that happened to be next door to a barricade. The soldiers

thought a shot had been fired at them from that house, and

they massacred

apparently all the men in the house, a lot of the other people,

too.

Or his drawings of the traveling

clowns, the Saltimbanques,

who became, in the nineteenth century, a persecuted entertainer,

and would really find it very hard to make a living. So Daumier's work

was one example.

|

|

Honoré Daumier, Saltimbanques

|

Much

of Baudelaire's

poetry is pitched against the authorities in protest at the conditions

of the urban poor. This is most explicit in his series on wine

and in his blasphemous poems like "Litany to Satan."

Yet there are theorists like Marshall Berman who think that this

opposition of Baudelaire's went, continued right through his

life, and Berman writes on the short prose piece, "The Eyes

of the Poor," from Paris

Spleen, as an example of Baudelaire's continuing political

commitment.

Now, you might be wondering whether these

angry representations achieved anything. Did Baudelaire's poetry

change the conditions which

provoked it and, if not, then what is the point of this iconoclasm?

But I think it's important, on some level, also to be able to separate

representation from impact. Like some other art, avant-garde works

provide images of conditions which otherwise would just be regarded

as statistics. They give us a representation of what things were

like then, which may be enough.

And here's an example from the

Soviet Union. In the 1930s the son of the Russian poet Anna Akmatova

is imprisoned in a Soviet labour camp. With other prisoners' mothers

she waits outside in the winter cold in the hope, usually unfulfilled,

that she will learn something of her son's fate. Recognizing

her, another woman urges the poet to find a way to represent the

event. It's too dangerous at the time to be written down, let alone

published, so Akmatova composes the poem "Requiem" in

her head and memorizes it. And only after the conditions it

criticizes have

passed

does it become public.

The artistic

avant-garde has had very little impact on social or political structures

for this to be a justification

of its

aesthetic radicality.

And there continues to be no correspondence, really, between

aesthetic radicality and social impact, not in any measurable

form. Dadaism's extreme iconoclasm, Picasso's

Guernica, the political sloganeering of the Situationists,

the violent noise of 70s Punk Rock has no discernible impact

on political realities of the time. In fact, it would be easier

to argue the reverse

from the political conditions which followed each of these protests.

Yet these "failures" shouldn't be taken as proof

that the avant-garde never existed, nor that its actions were

futile. The economy may consume all opposition, government policy

may only

be deflected by exhaustion or the death of politicians, all cultural

protest is ignored, yet the production of antagonistic works

continues. Is it better to be producing something rather than

nothing? Well, not

according to Marcuse, whose notion of the "affirmative character

of culture" proposes that the representation of what

is bad about society alleviates that society from doing anything

about

it. The idea that if you picture something that's wrong with

society, you give the authority of that society an excuse

not to do anything about it.

|

|

|

|

On

Aspects of the Avant-garde | Table

of Images

Contributor's

Notes |