JOHN RAVENAL | Recently Acquired, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Light-Based Art: Work by Finch and Navarro

Two new works of light-based art represent a promising development in the holdings of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA). Pieces by Spencer Finch and Ivan Navarro add stunning examples of new media and installation art, both nascent areas of the museum’s collection. The two works were made for the 2006 exhibition Artificial Light (co-organized by VCUarts Anderson Gallery and VMFA, and also shown in Miami at the Museum of Contemporary Art). I’m delighted that VMFA can share these pieces with our audiences in perpetuity.

The focus on light is particularly appropriate for an “encyclopedic” art museum. Light has long fascinated artists as a material and a subject: gold backgrounds of Byzantine mosaics, Medieval stained glass, Baroque contrasts of light and dark, and fractured reflections of Impressionism.

With the advent of electricity, artificial light entered into the artistic mix. From the late 19th–through the 20th–century, artists used various forms of light to explore a range of psychological, emotional, formal, and intellectual concerns. These include Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy’s 1920s kinetic Light Space Modulator. In the 1960s, Dan Flavin, Bruce Nauman, and James Turrell used fluorescent, neon, and natural light to plumb phenomenological depths. In the 1970s and ’80s, Jenny Holzer, Tatsuo Miyajima, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres expanded light art’s range of content with politics, philosophy, and personal history. The two new works by Finch and Navarro build on this entire legacy. (The Artificial Light catalogue is a good source for further information on this history.)

Spencer Finch, Kaaterskill Falls (July 30, 2006, 12:37 PM), 2006

The first work is by Spencer Finch (American, born 1962), a mid-career artist based in New York who transforms his perceptions of the world into pure color and light. Finch has an extensive exhibition record, including a retrospective at Mass MOCA on view through spring 2008. Other works are in the permanent collections of the Guggenheim Museum, The Art Institute of Chicago, The Hirshhorn, and the High.

Though Finch’s finished pieces appear abstract, his content always refers to something recently seen or something held in his memory. In addition, Finch often chooses subjects with historical, literary, or artistic associations.

|

Spencer Finch, (American, 1962– )

Kaaterskill Falls (July 30, 2006, 12:37 PM), 2006

Fluorescent light boxes with laminated filters

Two parts: 74"H x 50"W x 8"D

187.96 cm x 127 cm x 20.32 cm

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. The National Endowment for the Arts Fund for American Art.

Photo: © Travis Fullerton |

Kaaterskill Falls (July 30, 2006, 12:37 PM) uses light and color to represent the artist’s experience of the famous two-tiered waterfall in upstate New York. This was a popular subject for nineteenth-century writers and artists. Shown below is Hudson River School painter Thomas Cole’s image from 1836. Perhaps most well known is Asher Durand’s Kindred Spirits, which shows the falls in the distance.

|

|

| Thomas Cole (American 1802–1848)

Falls of Kaaterskill

1826

Oil on canvas

43 x 36 in (109.2 x 91.4 cm)

Warner Collection, Tuscallosa, Alabama

|

Asher Duran (American 1796–1886)

Kindred Spirits

1849

Oil on canvas

48 x 36 in (116.8 x 91.4 cm)

The New York Public Library, New York City

Eulogzing Thomas Cole, Duran’s painting depicts Cole with William Cullen Bryant. |

For 19th century artists, unspoiled American wilderness and the awesome spectacle of its natural phenomena confirmed their view of God in nature. Joined with an interest in radiant light, they sought to express the concept of the sublime. Finch is also interested in sublime light and natural spectacle, but he addresses these with a contemporary sensibility, incorporating science and abstraction.

|

Kaaterskill Falls in the eastern Catskill Mountains of New York.

A subject for painters of the Hudson River School and the inspiration for William Cullen Bryant’s poem, “Catterskill Falls.” |

When Finch visited the falls, seen here photographed from their base, he measured the light with his colorometer—a handheld device that analyzes hue, saturation, and luminance. Back in the studio, he recreated that exact effect of light using a spectrum of colored gels and fluorescent lights. A visitor standing before this work now experiences the exact same quality of light that Finch experienced at the falls on July 30, 2006, at 12:37 PM.

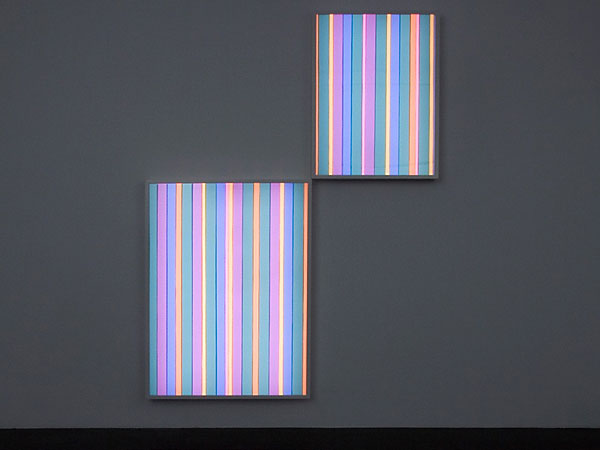

The pair of boxes, arranged vertically and corner to corner, refer to the two-tiered and staggered configuration of the falls. Here you see the piece installed at VCU’s Anderson Gallery with its reflection on the polished floor.

|

Spencer Finch, (American, 1962– )

Kaaterskill Falls (July 30, 2006, 12:37 PM), 2006

Photo: © Travis Fullerton |

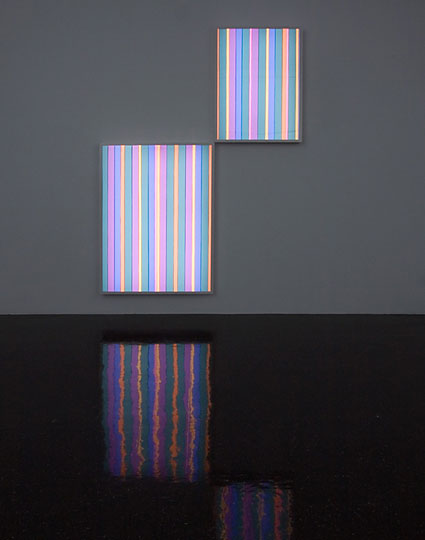

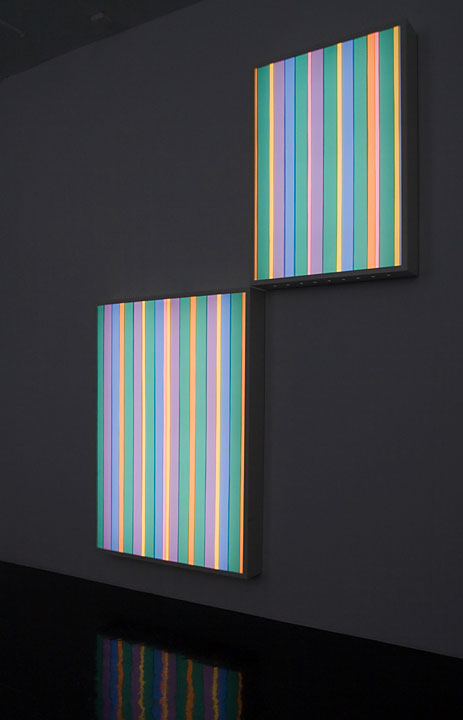

Here’s another view from the side.

|

Spencer Finch, (American, 1962– )

Kaaterskill Falls (July 30, 2006, 12:37 PM), 2006

Photo: © Travis Fullerton |

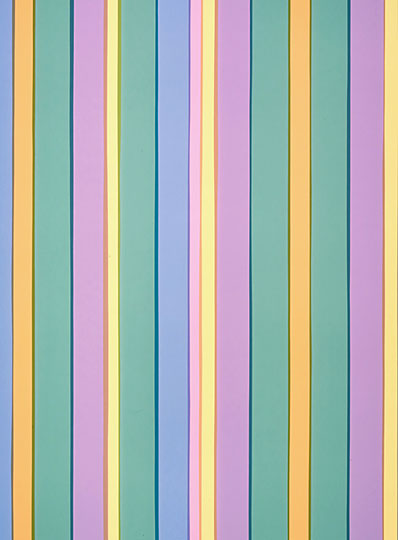

Finch hand cut the gels to give them a fluid edge and arranged them vertically like falling water.

|

Spencer Finch, (American, 1962– )

detail of Kaaterskill Falls (July 30, 2006, 12:37 PM), 2006

Photo: © Travis Fullerton |

The finished piece resembles a color field painting, such as this work by Morris Louis, Claustral (1961), from VMFA’s permanent collection.

|

Morris Louis (American, 1912–1962)

Claustral, 1961

Oil on canvas

85”H x 64½”W

215.8 cm x 163.8 cm

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond.

Gift of Sydney and Francis Lewis.

Photo: Ron Jennings © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts |

Finch’s work joins this style of non-objective art with the tradition of American landscape painting, making a work that is both highly abstract and highly referential.

With his interest in light and its connection to the 19th-century tradition of sublime landscape, Finch might seem to be a very late Romantic. But his belatedness to the tradition lends his work a wistful quality, even as its contemporary materials and electric glow ground it in the immediate present.

Ivan Navarro, Black Electric Chair, 2006

The second piece is by Chilean artist, Ivan Navarro (b. 1972). Several years ago, Navarro moved from Santiago to New York, where he now lives and works. His visibility has increased dramatically, and his work recently entered the Hirshhorn Museum’s collection and is in important private collections such as Saatchi, Marty Margulies, and Peter Norton.

|

Ivan Navarro, (Chilean, 1972– )

Black Electric Chair, 2006

Neon black light and electric energy

Number 2 of an edition 3 + 1 AP

27¾”H x 30⅜”W x 30¼”D

70.49 cm x 77.15 cm x 76.84 cm

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. The Kathleen Boone Samuels Memorial Fund.

Photo: © Travis Fullerton |

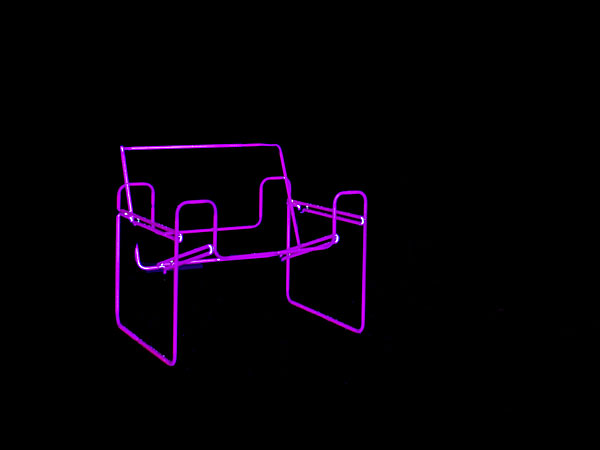

Navarro’s Black Electric Chair continues his interest in Modernist furniture by recreating Marcel Breuer’s iconic Wassily Chair—that symbol of early 20th-century industrial heroism and engineering inventiveness, which became, by the century’s end, a standard item in corporate lobbies and public waiting rooms.

|

Marcel Breuer

Wassily Chair |

In an earlier piece, Navarro re-made Gerrit Rietveld’s famous Red and Blue Chair using colored fluorescent tubes.

|

Ivan Navarro, (Chilean, 1972– )

Red and Blue Chair

|

Growing up in Chile during the 1970s and 1980s under Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship—a rule maintained by covert violence, intimidation, and disinformation—gave Navarro a particular interest in power and double meaning. While he is truly fascinated by the beauty and seduction of colored light and clean Modernist design, his works also surge with undercurrents of darkness.

A piece called the Briefcase (Four American Citizens Killed by Pinochet, 2004) contains glowing bulbs with the names of four victims of political assassination.

|

Ivan Navarro, (Chilean, 1972– )

Briefcase (Four American Citizens Killed by Pinochet) |

Homeless Lamp is a piece on wheels that draws its power from street lamps like a wandering parasite, addressing landlessness and loss of identity, common Latin American themes.

|

Ivan Navarro, (Chilean, 1972– )

Homeless Lamp |

Floor Hole (2005) suggests a disquieting void opening up beneath the floor.

|

Ivan Navarro, (Chilean, 1972– )

Floor Hole

|

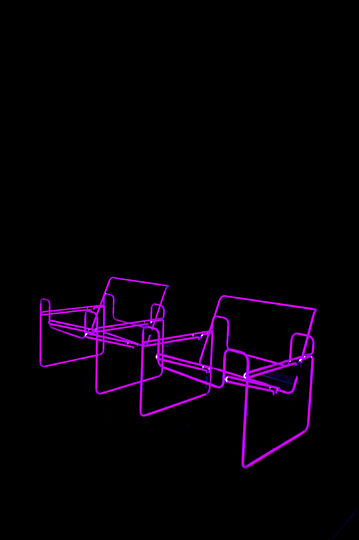

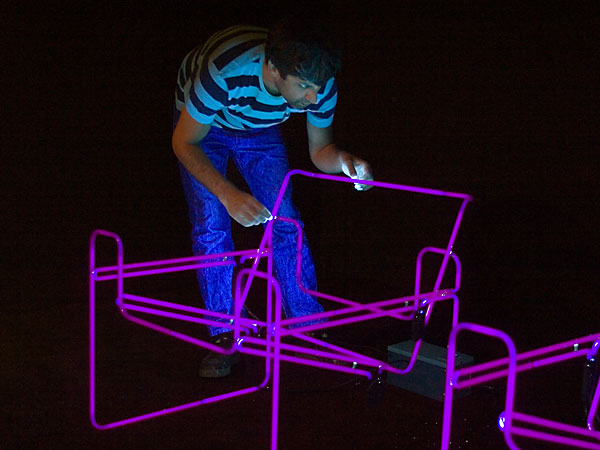

Even so elegant and apparently benign a work as Black Electric Chair contains an emotional jolt. Originally displayed as a pair in an all black room with carpeted floor, this work is opulently visual in its use of “black light”—a filtering of the full spectrum that causes phosphors in natural and manmade materials, such as teeth, eyes, and some white clothing, to appear unnaturally bright, while the bulb itself emits only a faint purple radiance. (You can see the strong glow on the artist during installation.)

|

Ivan Navarro, (Chilean, 1972– )

Black Electric Chair, 2006

Photo: © Travis Fullerton |

|

Ivan Navarro, (Chilean, 1972– )

Black Electric Chair, 2006

Photo: © Travis Fullerton |

Navarro’s version of the Wassily Chair transforms the stripped-down tubular steel frame of the original into a delicate tracery of lighted lines in space. The work has a virtual quality, like a blueprint for future production. At the same time, remaking Breuer’s chair in glowing light seems to complete the original, as if it required electricity to tease out unstated implications. Breuer had said about his Wassily Chair that he “regarded these shining, sweeping lines not only as symbols of technology but as technology itself.” He considered the chair a machine for sitting, to shape “new man” by encouraging a relaxed but disciplined posture that others equated to the low, folded position of a race-car driver. Navarro’s Black Electric Chair creates a tension between the chair’s invitation to relax and the eerie, even sinister, implications of its electrified glow. Efflorescing softly in the dark, it transforms the Modernist dream of perfecting life by new technology into a phantasm.

Risks of Preservation and Display

Along with its obvious allure, light-based work presents difficulties for museum preservation and display. Issues arose during the acquisition process that required further research. How long will the bulbs last? Will the materials be replaceable in case of deterioration or accident? Will replacements produce exactly the same light? These questions and more required satisfactory answers before the works could be routed through the usual approval process of Director, Art Acquisitions Committee, and full Board of Trustees. Finch’s bulbs, “high-end Dutch fluorescents, calibrated to always emit the same light,” should last at least 20,000 hours. Navarro’s neon has a lifespan of 80,000 hours. Given the usual rotation of works on display, Finch’s original bulbs should last many decades and Navarro’s possibly for centuries. As a precaution, we plan to buy backup bulbs for Finch’s piece, and Navarro’s glass tubes can be re-pumped with gas for another 80,000 hours.

So yes, these works do pose risks and limitations. They aren’t granite steles, or even oil on well-primed canvas. But nor are they the most fragile works in the collection. The risks seems far outweighed by the reward. As works of new media and installation art—each installed, ideally, in its own room. Kaaterskill Falls and Black Electric Chair show how contemporary artists have branched well beyond conventional media of paint on canvas and bronze, wood, or stone sculpture. Light is among the most important of the new media used by artists today, and I’m pleased to have acquired works that help broaden the museum’s contemporary holdings in this area.

Contributor’s Notes

return to top

|