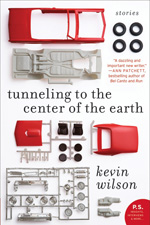

Review | Tunneling to the Center of the Earth by Kevin Wilson

Harper Perennial, 2009

|

|

|

|

Already, in his first collection, Kevin Wilson could teach his generation of fiction writers a thing or two about magical realism and a currently stylish form of short story, characterized by a distinct narrative voice, using the present tense, and a rather self-conscious tone, as if the story itself wants the reader to be aware of the author’s presence. In lesser hands, such stories may include gratuitous gore, fantastical creatures, strange situations, made-up language, and any number of other inventions put together in whatever narrative order, or lack thereof, seems best. While Wilson also inhabits an absurd universe, his eleven stories in Tunneling to the Center of the Earth are both startling and persuasive, drawing the reader into a world at once completely insane and easy to believe in. The bitter edge which underlines Wilson’s deadpan writing oddly makes the fantastic elements more persuasive.

Wilson fits the craziness to the situation, so that each element seems to be a product of the other rather than random imaginary pieces. This technique is evident in stories such as “The Shooting Man,” where a small-town hick becomes obsessed with a sideshow that depicts a man killing himself onstage every night, and in “Mortal Kombat,” in which two teenage boys are horrified to discover their homosexual tendencies, beating each other up as they do so. Wilson credibly takes on various voices, as in “Grand Stand-In,” where the elderly female narrator takes a job as a grandparent for hire. He even gets away with the always-controversial use of the second person in “The Choir Director Affair (The Baby’s Teeth),” in which a couple doomed for adultery and divorce has a new baby with a perfectly formed set of choppers.

The title story is a deft example of how Wilson puts it all together in a convincing, delightful way. Wilson describes three recent college graduates who, when presented with the boring and rather bleak prospect of entering the adult world, decide instead to turn their energy to digging a hole. However, they soon realize that there are practical hindrances to digging indefinitely downward: one character dreams that he “had felt the earth give easily under his shovel and that fire had come out of the cracks, spilling around his feet;” he worries, “We’ll find mole people or molten lava or some underground ocean.” The three responsibly avoid these concerns by simply digging sideways, working all summer to create an underground labyrinth below their otherwise ordinary suburban neighborhood.

They find

time capsules that had been forgotten and never dug up. . . a surprising number of jars filled with money. . . stuffed full of moldy tens and twenties, folded and wrapped in rubber bands, the jars sealed tight with paraffin wax. . . animal bones and human bones, and the still-decomposing body of Jasper Cooley, a drunk who had disappeared a few months ago.

The reader is thus treated to the vicarious pleasure of hollowing out a secret place, a place undreamed of by the citizens of the mundane landscape above.

Wilson is good at finding the humor in his own inventions. The narrator’s parents are worried but supportive: “We hope it’s nothing we’ve done, but we just want you to be happy. So, if you need to be underground to be happy, that’s fine with us.”

If the reader is lured in by the expert inventiveness of the worlds Wilson creates, he also persuades us by the very real emotions he conveys. Wilson depicts feelings that are so easily recognizable as our own that the pain is quick, surprising in its sharply handled description, and somehow more manageable as a result. In “Blowing Up on the Spot” the narrator opens with this grim announcement: “I count my steps because I have a boring and unhappy life.” He goes on to describe an occupation that is fittingly illustrative: he is a sorter of Scrabble tiles, working in one of four rooms, each containing “a mountain of wooden tiles, which fall in clumps from an overhead chute;” our worker is assigned the letter Q. The misery of such a calling is wonderfully appropriate: “I wade around in the alphabet, up to my knees, and search for Q’s. It is not a glamorous job.”

We discover that, as a result of the spontaneous combustion of their parents three years earlier, the narrator’s younger brother, a star on his high school swim team, has a habit of attempting suicide: “Caleb has tried to kill himself twice in the three years since our parents died. The last time, he slit his wrists with a Swiss Army knife during practice and dove in the pool to swim a hundred-meter freestyle, trailing a cloud of blood behind him.” You wouldn’t think you could feel real pain at the effects of spontaneous combustion, but Wilson’s imagery makes it real.

The language of the stories carefully reflects their nature, as well. The narrator of “Blowing Up On the Spot” happens to live over a confectionery, where a delicious woman named Joan “smells of sweat and burned sugar, of a fancy dessert that you set on fire, cherries flambé.” Joan’s “smile creeps across her face in small increments, as if her happiness starts in one place and slowly moves out in all directions. . . . Pecans, chocolate, and caramel mix together in my mouth and I taste Joan’s fingerprints on my tongue.” Thus Wilson’s imagery all begins to work together, in spite of the varying connotations: Caleb’s blood in the pool, Joan’s burning scent, the melting candy, and the carefully counted steps the narrator actually does take every day on the way to work, all work together to create one consistent, utterly believable life.

Not only does Wilson accomplish the task of persuading the reader to believe in the impossible, he also convinces us to participate and understand, even when the scenario is more than a little inappropriate, if not downright illegal. In “Go, Fight, Win” the sixteen-year-old Penny is gently bullied onto the cheerleading squad by her mother—“You’re pretty, Pen, real pretty . . . the kind of pretty that would benefit from being a cheerleader, you know?” Penny makes the tryouts, but hates cheerleading: “She hadn’t made any new friends and the one thing she’d always depended on, the ability to disappear, was gone.” Instead of using her prettiness to become popular, Penny develops a fascination with the twelve-year-old boy next door, a child who loves things like jumping off the roof and setting things on fire. It’s easy to imagine this scenario ending as a morality tale, a caution of the kind of disaster that can occur when unlike things try to fit together. But Wilson has his characters keep trying, as if to say that even if this is far from our idea of romance, it is important, and we should respect it—in spite of high school football, parental disapproval, and third-degree burns.

Wilson has been publishing like a pro for many years, his work appearing in the best literary journals with the abundance usually associated with poetry rather than fiction. Tunneling to the Center of the Earth might be Kevin Wilson’s first book, but his creative invention, expertise at transmitting emotions, and sharp sense of humor all testify that he has not been an amateur for quite some time. ![]()

Kevin Wilson’s work has been published in numerous journals, including Ploughshares and One Story, and his fiction has been anthologized in New Stories from the South: The Year’s Best (Algonquin, 2005 and 2006). Wilson has received fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, and the KHN Center for the arts. He teaches at the University of the South.

Contributor’s

notes

Review | The Lost Books of the Odyssey, by Zachary Mason

Reviews